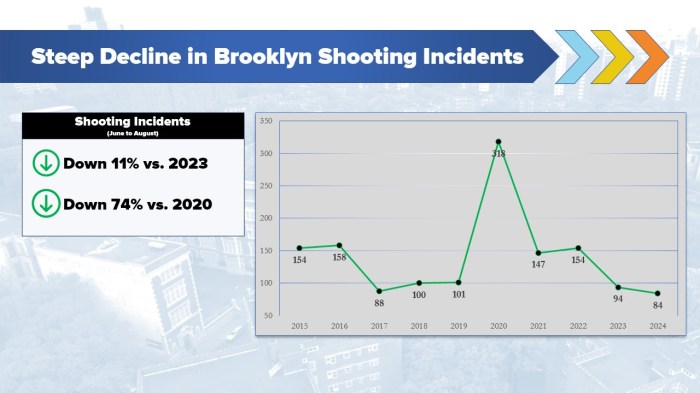

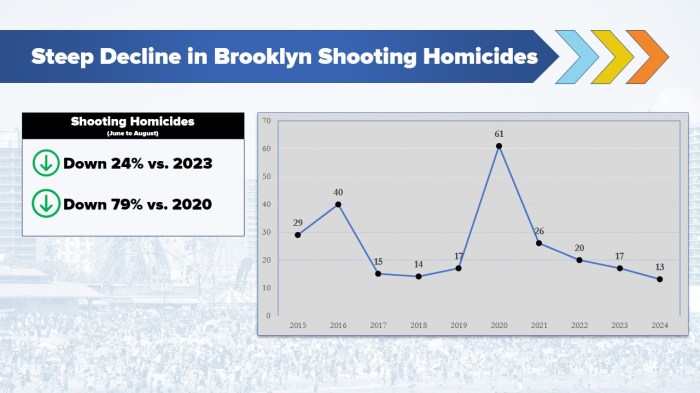

This summer was one of the safest in recent history in terms of gun violence and gun-related deaths, according to data released Friday by Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez’s office.

The months of June, July, and August are typically marked by high numbers of shootings and gun-related deaths, but this year, Brooklyn reached its lowest levels, Gonzalez said.

The borough recorded 13 gun-related homicides this summer — a 24% decrease from 2023 — and 84 shootings, down 11%. And while the number of shooting victims increased by three, it marks the second-lowest total in that category after last summer.

“The summer months are traditionally the time when gun violence spikes, which is the reason the NYPD and my office focus extra resources and efforts during that period,” Gonzalez said in a statement. “It is gratifying that, after a particularly safe summer in 2023, we reached even more historic lows this year.”

These numbers reflect the lowest recorded stats since data has been collected, according to the DA’s office, and represent a 74% decline compared to the summer of 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic, civil unrest and a spike in violence occurred concurrently.

Shooting deaths also reached the lowest level ever recorded with 13 — a 79% decline compared to 2020.

“While more needs to be done, public safety in Brooklyn continues to improve and our multi-pronged approach in fighting gun crimes – which includes gang takedowns, investments in our Digital Evidence Lab, precision prosecutions, and community-based initiatives – is working,” Gonzalez said.

Jibreel Jalloh, the founder of The Flossy Organization, a cure-violence organization in Canarsie, called the DA’s report “promising.”

“While this decline is a strong step forward, we must remain focused on our ultimate goal: ending gun violence,” Jalloh told Brooklyn Paper. “The 13 lives lost are 13 too many.”

The DA’s office attributed the violence reduction in part to successful Supreme Court convictions, gang takedowns and gun buy-back events.

Jalloh said the city could see an even greater decline with the increased investment in cure-groups and programs, such as Flossy, Man Up and Save Our Streets (S.O.S.). Following the pandemic, the city expanded the work of crisis management centers with the growth of violence interrupters and mentors who mediate potentially violent situations and work towards peaceful solutions.

“The city has a list of evidence-proven methods to stop shootings,” Jalloh said. “We just need government leaders that have the courage to invest in those programs fully.”

These initiatives, however, are not a cure-all.

Despite organizational efforts, the number of borough-wide shooting victims — 104 — rose slightly, up 2.9% compared to the same time last year. Still, that number was the lowest on record for a summer of gun violence recorded by the DA’s office.

Community advocates have argued a lack of adequate resources feeds the growth of violence. They believe the city can absolve itself of violence by closing wage, health and education gaps.

“We need deeper investments that strike at the root causes of violence—lack of opportunity, poverty, unemployment, and poor education,” Jalloh told Brooklyn Paper. “Let’s honor the memory [of those who’ve died to gun violence] and families by committing to the necessary investments today so we can build on this progress tomorrow.”