City agencies behind the design of the new 15-story, 1,040-bed Brooklyn Borough Jail in Boerum Hill have reneged on commitments made to the community during the land use review process, compromising the jail’s ability to integrate safely into the neighborhood, locals said at a community board meeting Wednesday night.

Specifically, underground parking for the planned 712,150-square-foot development has been cut from 292 spaces to 100 (which can only be used for authorized vehicles, not staff cars) and plans for a second tunnel between the courthouse and the jail have been dropped. Those factors would likely result in State and Smith streets being backed up with NYPD, corrections, and regular traffic, as well transfers of those in custody happening at street level, people said at the meeting.

Concerns were also raised about the number of beds in the jail increasing from a planned 886 to 1,040, at the direction of the Adams administration, through the addition of mezzanine floors, ultimately decreasing the space prisoners have. There was concern that space had come through slashing the number of therapeutic beds for inmates with mental health issues, which must be on a single floor.

The plans for the new facility, which will replace the out-of-use Brooklyn Detention Center at 275 Atlantic Street, were presented by representatives from the city’s Department Design & Construction, Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice, Department of Correction, and the project’s design-build team at an in-person Community Board 2 land use subcommittee meeting in Downtown Brooklyn Wednesday night.

A DDC rep told meeting-goers budget pressures were behind the parking cuts. He denied space-saving for the extra beds came from cutting therapeutic beds and said it was a policy decision, and said he had no knowledge of the previously planned second tunnel.

But not everyone was convinced. “This is a $3 billion building, when they talk about budget cuts, $3 billion is $3 million per bed,” said Justin Pollock, a rep from residential building 87 Smith Street. “It is the most expensive constructed building per square foot in the United States. So it’s incredible that they’re making budget cuts on this, when they’re spending this much money per bed to build a jail.”

Pollock said he had been attending meetings on the jail for years and had advocated, along with other local residents and electeds, for key commitments in the ULURP process including the 292 parking spaces, an efficient sallyport system that removed traffic from the street, the extra tunnel so transfers don’t occur at street level, and a smaller, safer jail for those incarcerated inside.

“The community board is trying to make this jail work for the neighborhood, as well as the jail system to work,” he said, adding later the community was not at all against a jail. Instead, it was against the changes that were compromising “the efficiency and the effectiveness of this jail,” such as reducing therapeutic beds and increasing the overall population with tiered mezzanine floors, which he said were more cramped and reduced staff oversight.

“I think you understand where I’m going with this and understand what they’re not doing and what they’re taking away. And I think you should be very concerned about what else they’re taking away,” Pollock told subcommittee members.

He said if NYPD transfers continue to happen at street level, when children look out of the windows of the planned children’s area on State Street, “they’re going to be seeing more people in shackles on State Street and that’s what we need to work on.”

Architecture firm HOK is largely behind the design of the $3 billion facility and, along with city agencies, has held two public design sessions this year. The plans and renderings presented at Wednesday’s meeting were informed by those sessions and the “integrated and iterative process,” HOK FAIA Kenneth Drucker said.

Renderings show the block-long jail appears similar to a tall luxury rental or condo development, contrasting with the more low-rise historic builds of surrounding Boerum Hill, Cobble Hill, and Brooklyn (an issue that was brought up by local residents.)

“It’s really important for the entire team that this building is knitted to the fabric of Brooklyn,” Drucker said. He added the project was guided by principles of bringing natural light deep into the building, creating a civic asset, providing access to the outdoors for all users, and providing access to healthcare and education.

“And the idea is that we want to use a warm palette of materials, natural materials, the use of color and texture that are Brooklyn. And we want to normalize the space.”

HOK has worked on a range of justice system facilities across the country, including in patient treatment centers, court houses, and prisons. Drucker said a key reason the borough-based jails were being built to replace the troubled Rikers Island complex was to make it easier for families and the community to visit their loved ones, and the team was taking special care to make those spaces inviting.

Incorporated in the design are a landscaped pedestrian plaza, outdoor seating, cycling infrastructure, traffic calming devices, and as much greenery as possible, HOK landscape architect Autumn Visconti said. The “therapeutic designed landscapes” were for those in custody, visitors, and the public, she said, and were in tune with the surrounding Downtown Brooklyn streetscape.

The entrance to the jail will be through a large open lobby on Boerum Street, while there will be a 30,000 square foot community space (it’s use is yet to be decided) accessible from Atlantic Avenue. Staff access to the building will be at State Street.

There was a lot of talk at the meeting about how the building interfaces with Atlantic Avenue and how traffic will be managed around Atlantic Avenue and Boerum Street. Visconti said the design team had widened the Atlantic Avenue sidewalk throughout the design process and introduced traffic calming measures, and would be continuing to work on lighting, stormwater management, and the introduction of security measures such as bollards.

However, she said, the team was trying to integrate security infrastructure into the landscape as seamlessly as possible to avoid the “post-9/11 aspect of security design.”

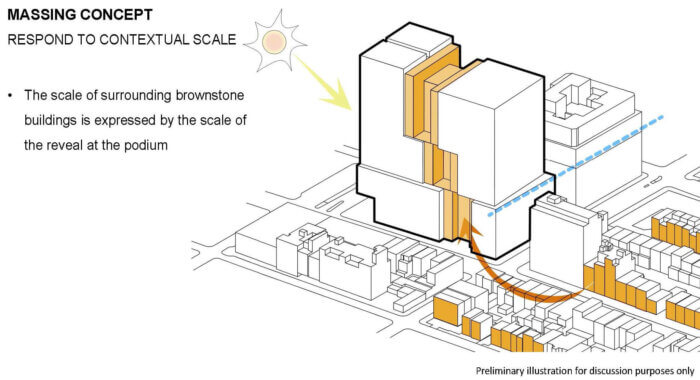

Meanwhile, the facade of the building and its massing has been informed by the articulation of the area’s brownstones and the architecture on existing civic buildings in Downtown Brooklyn, HOK design principal Aman Krishan said. She said the team had taken ideas from a traditional brownstone and “interpreted that through a modern language” resulting in paneling across the facade that reflects the “rhythm of brownstones” and some cornice detailing.

The building has a carve out at the center, dubbed the central reveal, that breaks up the massing of the large structure and allows natural light into recreation spaces. Krishan said the windows on that reveal were a nod to the double hung windows of brownstones, and the reveal itself was being done in a warm color seen across the surrounding neighborhoods.

“We’ve designed this facility for growth and change and think about this as an optimistic architectural intervention for the community and for its users,” she said. That includes having a horticulture space for those incarcerated at the jail, and a public art component that is being planned by the Department of Cultural Affairs and will be brought to the community at a later stage.

Members of the land use subcommittee had a range of questions that largely centered around where staff, visitors, and locals would park in the area, and what effect the increased traffic would have on the neighborhood. Concerns were also raised about the scale of the building.

“This building is wildly out of context, wildly out of context,” Daughtry Carstarphen said, adding that while there were a lot of good things about it, “you just need to scale the building down to half the size and then I would sign off on it.”

“This building was promised with 886 beds, that has increased to 1040. I think that it’s a stretch to say that you’re relating to the neighborhood around the building.”

Concerns were also raised about whether Smith and State street residents would be in the line of sight to those in the jail and be affected by the acoustics of the recreation rooms. “I’m just speaking from previous experience,” a member of the public said. “It was not unusual to be sitting on my deck eating dinner with the guys playing basketball yelling down at us.”

The new jail is a fundamental part of the city’s plan to close the failing Rikers Island jail, where at least eight inmates have died this year. In 2017, then-Mayor Bill de Blasio proposed four new jails — one in each borough except for Staten Island – under a scheme that would reduce the number of detainees while providing easier access for families and lawyers.

Initial plans for a 20- to 40-story, 395-feet-tall building on the Atlantic Avenue site, and similar towers in the other three boroughs, were met with instant community backlash. Prior to the land use review process, which was completed in 2019, the city pulled back on those plans of 1,400-plus bed jail to one housing 886 people.

While the plan was adopted by the Adams administration, the mayor has since called it “unworkable” and added beds to each of the proposed jails. Even with the additional beds, the four jails will hold 3,300 prisoners, far less than the more than 6,000 capacity currently in the city.

In response to a question on this, a member of the mayor’s team said at the meeting the city was also operating a number of programs in conjunction with the building of the new jails that are designed to decrease the population of people incarcerated in New York by lowering recidivism rates and increasing alternatives to jail time.

A member of the public commented that those programs should have been implemented before any new jails were planned, and a higher number of smaller jails should have been built to provide the best environment for those incarcerated and staff.

Meanwhile, plans for the actual construction of the new Brooklyn jail have been marred with delays, and despite Rikers Island having a closing deadline of 2027, the new jail won’t be finished until 2029, the city says. Earlier this month, an application for a new-building permit was filed with the Department of Buildings for the 15-story, 339-foot-tall building with NYC DDC listed as the building’s owner.

Although missing a quorum, the subcommittee voted to move the plans forward to the next stage of the design approval process and issue a letter of conditional support with recommendations for the design. (The project went through ULURP in 2019.) Next, the design team will present the plans to the Public Design Commission, hold more public design workshops, and come back to the board again in winter and spring.

The subcommittee’s slew of recommendations include requiring a Department of Transportation rep be present at the next meeting to answer the range of questions on the impact on traffic. The next meeting will be held at the start of next year.

This story first appeared on Brooklyn Paper’s sister site Brownstoner.