The family of Delrawn Small, a Black man killed by an off-duty police officer in East New York in 2016, says that the Police Benevolent Association, the powerful NYPD patrol officers’ union, is attempting to derail a planned disciplinary trial for the officer who killed Small. On Thursday, his loved ones plead with Mayor Eric Adams and NYPD Commissioner Keechant Sewell to allow proceedings to go forward.

The same day, 26 elected officials, including 14 representing Brooklyn, sent a letter to Adams and Sewell urging them to allow the disciplinary trial, which the Civilian Complaint Review Board is hoping to soon commence, to proceed.

“The twenty-six elected officials signed on to this letter urge you to allow the CCRB to do its job and continue with the disciplinary proceeding against Mr. Isaacs,” the letter reads. “We respectfully request that you reject the PBA’s latest attempt to thwart fairness. Removing the CCRB from this case at this stage, after 5 and a half years, would undermine faith in government.”

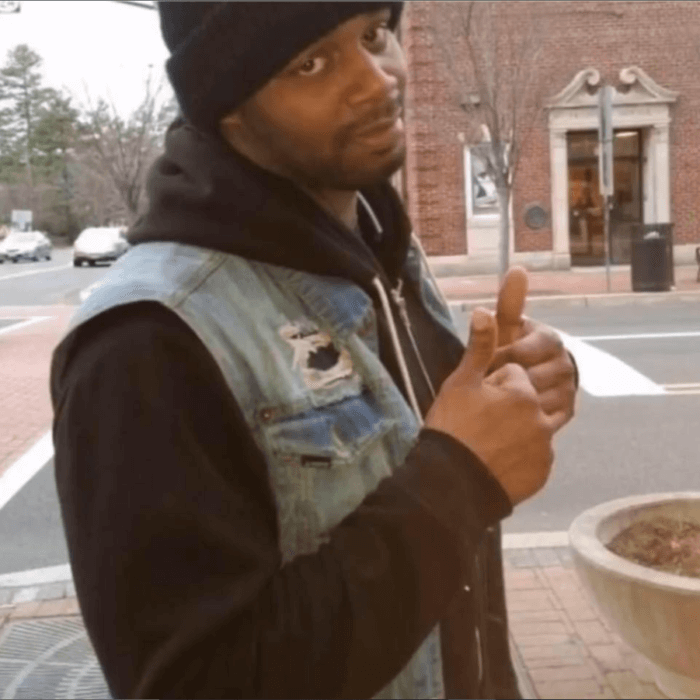

Small was killed on July 4, 2016 by off-duty NYPD Officer Wayne Isaacs while both were sitting at a stoplight at Atlantic Avenue and Bradford Street in East New York. Isaacs and the NYPD initially claimed that Small, in a fit of road rage, had approached the officer, cursed him out, and punched him before Isaacs fired the fatal shots. But surveillance video uncovered several days later cast doubt on the department’s account of the incident, showing Small, who was unarmed and traveling with his girlfriend, step-daughter, and newborn baby, collapse to the ground within seconds of approaching Isaacs’ vehicle.

The family says that after Isaacs shot Small, he neglected to render emergency aid and instead called 911, in the process obscuring his role in the incident by withholding the fact he had shot him and that he was bleeding out in the street. They say that aspect of the encounter in particular should make it an open-and-shut case against Isaacs.

“There’s a video out that shows how he murdered our brother,” said Victor Dempsey, Small’s younger brother, at a March 31 press conference at City Hall with allied elected officials and advocates. “But what folks tend to forget is before the video surfaced, he lied.”

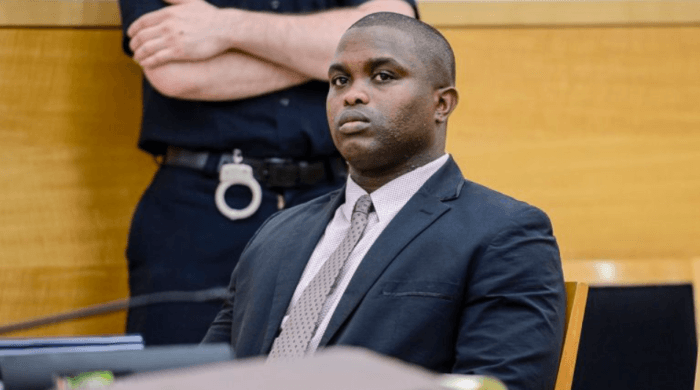

Isaacs was acquitted by a jury of second-degree murder and first-degree manslaughter in 2017, and was later cleared of wrongdoing by an internal NYPD investigation; he remains on the force and has returned to active duty. But the CCRB announced in 2020 that it had substantiated an excessive force complaint and Isaacs and in January of last year announced its intention to bring disciplinary charges against the boy in blue. Last month, a judge tossed Isaacs’ appeal to prevent the disciplinary proceedings from moving forward.

While the CCRB was granted the ability last year to initiate its own investigations, it is only empowered to act as a prosecutor in internal NYPD disciplinary trials, and final authority to actually mete out discipline rests with the commissioner, who ignores CCRB disciplinary recommendations in a majority of cases. The police commissioner is also empowered to “retain” any disciplinary case and withhold the CCRB from any involvement, an agency spokesperson told Brooklyn Paper, noting that that provision of the city charter is what lawyers for Isaacs provided by the PBA are currently attempting to exploit.

“The CCRB maintains that Officer Wayne Isaacs committed misconduct when he shot and killed Delrawn Small,” the CCRB spokesperson said in a statement. “We believe the evidence is clear and will argue the case to Commissioner Sewell and the Trial Commissioner when our Administrative Prosecution Unit takes Officer Isaacs to trial. Mr. Small’s family has waited nearly 6 years to see Officer Isaacs held accountable for his fatal misconduct and the CCRB is committed to moving forward with this case.”

Small’s family says they have not had any communication with either the mayor or the police commissioner, and only found out about the PBA’s attempt to nuke the proceedings from the CCRB — and they say it’s just the latest in a long saga by the controversial police union to stonewall any attempt to hold Isaacs accountable.

“The police union lawyers are throwing spaghetti at the wall, hoping something sticks,” Dempsey said. “And they’ve been doing that since the day he murdered our brother.”

In a statement, PBA president Pat Lynch said that allowing the case to proceed would not add anything new to the case considering it had already been adjudicated by the NYPD internally and by a Brooklyn jury.

“CCRB has nothing new to add to this case, which has already been fully investigated and adjudicated by the NYPD,” Lynch said. “The police officer was also acquitted by a Brooklyn jury. CCRB is simply looking for a third bite at the apple in order to justify their bloated budget and advance their anti-cop agenda.”

A PBA spokesperson disputed Small family claims that the union was attempting to discharge the case via a “backroom” deal, arguing that Isaacs’ lawyers are attempting to get the case dismissed on the same grounds they tried in court earlier this year, namely that the case has been previously adjudicated by the NYPD and therefore a new proceeding would be “arbitrary and capricious.”

Spokespersons for the NYPD did not respond to requests for comment from Brooklyn Paper. On Wednesday, Sewell declined to directly answer questions from Councilmember Sandy Nurse, who represents the neighborhood where Smalls was killed, on whether she believed the CCRB should be allowed to proceed, but said that “malfeasance and misfeasance” by members of the NYPD would not be tolerated under her watch.

“I certainly intend to hold every officer who does not follow the rules and regulations of this police department accountable,” Sewell told Nurse at the virtual oversight hearing on the mayor’s anti-gun violence blueprint. “So while that case has its own outcome and is still going through the process, I want to make it very clear that I will not and the mayor will not allow malfeasance or misfeasance on the part of any member of this police department to go unanswered.”

Sewell said that she intended to make a quick decision on the matter as soon as she was able to review it, though she did not provide a timeline. The CCRB spokesperson said that the watchdog agency also could not provide a timeline without greater clarity from the NYPD.

At Thursday’s rally at City Hall, Nurse and others expressed skepticism of Sewell’s claims, and questioned the point of the CCRB’s existence if it’s ability to try claims of excessive force can be pulled back by department brass.

“We have two legal systems,” Nurse said. “Why have the CCRB if we are not going to allow it to do its job, and fulfill its mission. It has a mandate, and it’s the least we have to hold accountability. And yet every time there seems to be an obstacle in the way of allowing it to do its job. What is the point?”

A spokesperson for the mayor’s office did not respond to a request for comment. Hizzoner told Brooklyn Paper in December after the CCRB was granted authority to initiate investigations that he would defer to existing law on such matters and that he wished to stay out of agency politics. The mayor has made public safety a linchpin of his young administration, resuscitating the controversial, disbanded anti-crime units and removing homeless people from subway trains in an effort to reduce violent crime.

But while Adams has said he doesn’t want abusive cops to mar his push for public safety, advocates say he has not prioritized the proliferation of public safety through holding officers accountable.

“It seems like we’re always trying to do something unreasonable, but we’re not. The system forces us to push and fight for just a basic semblance of justice,” said Public Advocate Jumaane Williams. “Mayor Adams, Commissioner Sewell, this did not happen on your watch, I’m clear about that. But what happens from here on, is on your watch.”

Dempsey and his sister, Victoria Davis, say that nearly six years since their brother’s death, the loss has had a tremendously difficult impact on the family, which would already be mourning the death of Small even if they managed to get Isaacs fired or convicted. They say that despite the pain and trauma caused by continually having to relitigate their brother’s killing, they are determined to prevent a similar tragedy from befalling another family.

“When you talk about our sacrifice and how it impacted us, we’re not victims,” Dempsey said. “We’re fighting for our brother, we’re fighting for the rest of the city. And we’re fighting for real change in public safety.”

“I’m never getting my brother back, my family will never get our brother back,” he continued. “We do this time and time again because it’s not right that we have murderous officers on the force that could potentially kill someone else.”