Long-suffering loft tenants are finally set to get relief under a new bill, signed into law last week by Gov. Kathy Hochul, allowing them to sue neglectful landlords in housing court — just like any other tenant already can.

Because lofts are constructed from former commercial or industrial spaces, there had been a long standing ambiguity in the legal system, and as a result, tenants were previously unable to sue their landlords in housing court to force basic repairs and maintenance of their living spaces.

Now, the law, which took effect on Dec. 1, will provide tenants of lofts (technically called “interim multiple dwellings” or IMDs) with much-needed recourse to combat porous buildings owners.

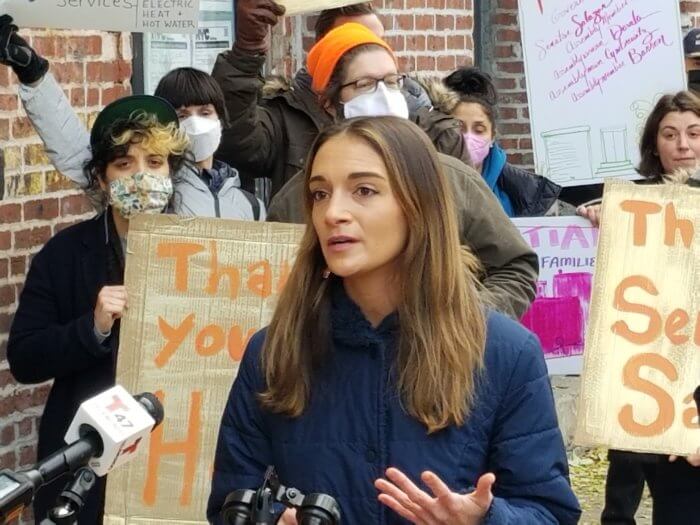

“Residents who live in loft buildings and tenants in live-work spaces, they’re unfortunately used to living in limbo, in many cases,” said northern Brooklyn State Sen. Julia Salazar, who sponsored the bill in Albany, at a press conference on Tuesday. “They’re used to having to fight for their rights as tenants to be recognized, and to have the same protections that other tenants already have. Loft tenants deserve to be protected, they deserve to have recourse when their landlord fails to maintain basic standards of safety and habitability in their apartments.”

For some tenants, like those living at 400 South Second St. in Williamsburg, the unequal status of their apartment has meant years without heat in the winter.

“My unit hasn’t had heat for…three years? It’s been sporadic, some winters on, some winters off,” said Nora Lardner, who has lived in the building for nine years. “We have space heaters, which just jacks up our electric bill unfortunately. The first winter it didn’t turn on, it got really cold that Thanksgiving. And I had guests staying with me from out of town, and everybody was in 15 sweaters and blankets.”

Lardner and her partner Jordan Christensen said they generally don’t get any responses from their landlord, which is registered under a limited partnership. In one instance, an electrical fire broke out in the apartment — but the landlord took three days to respond to their requests for repairs.

The glass front door to the building features a noticeable crack, which Lardner says has been there for about six months with no action by the landlord.

Aruna Naimji, who lives at 8-10 Grand Ave., said she hasn’t had gas in the apartment for three years.

“We’ve all been experiencing a kind of difficulty when our landlord decides they’re not going to take action and restore essential services like gas, electric, heat, hot water,” Naimji said. “I can tell you, it’s very difficult to try to convince your child to take a bath when it’s freezing in the house.”

Loft buildings tend to lack a residential certificate of occupancy, meaning anyone living in them previously could not adjudicate their claims in housing court, like most every other tenant in New York City. Instead, they had to bring any claims of wrongdoing to the Loft Board, a city commission created by the original 1982 Loft Law, whose main purpose for existing is to facilitate the legal conversion of lofts into safe, rent-stabilized residences, not to protect residents from neglectful landlords.

“I don’t want to fault the Loft Board too much because the Loft Board is pretty under-resourced,” Salazar told Brooklyn Paper. “And that’s something the city should take responsibility for, but regardless, I think that hopefully, this will help ease some of the burden on the Loft Board and certainly some of the burden on tenants, that they’ll be able to take these cases to housing court.”

Unlike the Loft Board, housing court is an actual court of law, whose orders have the force of law, as well as that of the Sheriff’s office, which serves as the court system’s law enforcement agency.

Salazar said that, because of the nature of lofts being semi-legal dwellings, it’s difficult to quantify exactly how many people actually live in them or will be affected by the new law — but, she said, the number is probably well into the thousands, with many seeing the same problems of neglectful landlords.

In Brooklyn, lofts are heavily concentrated in Williamsburg, where artists have historically taken over former industrial spaces as the neighborhood gentrified over the past two decades.

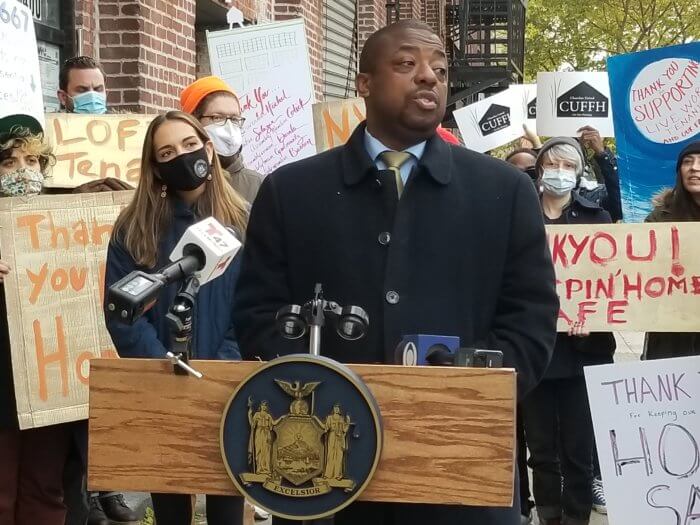

Lieutenant Gov. Brian Benjamin, who joined Salazar and others at the Tuesday press conference, said that the new law will also allow loft tenants to take advantage of housing reforms the state has enacted in recent years — such as universal right to counsel in housing court.

“Being provided an appropriate living space is not an amenity,” Benjamin said. “It should be a universal right. And that is what we are seeking to do.”