The Year of the Dragon is supposed to be a fruitful and auspicious year, according to the Chinese Zodiac — and plenty of brownstone Brooklyn foodies are hoping some of that luck goes toward improving their neighborhoods’ dismal Chinese food offerings.

It’s true: Brooklyn boasts a hot, spicy, and vibrant Chinese food scene in Sunset Park, known for hole-in-the-wall noodle shops like Yun Nan Flavor Snack Shop, banquet-style meccas like Lucky Eight, and fish-ball-hawkers like the Kalaka Cafe. But in the northern parts of the borough, there’s a devastating dearth of everything from pot stickers to pork buns.

Chinese restaurants in neighborhoods like Park Slope, Cobble Hill and Williamsburg have, for the most part, remained dreary, uninspiring delivery joints while their culinary neighbors have surged, gaining praise in the hometown press and beyond.

As is the case with most everything in the city, the problem with Chinese food in Brooklyn comes down to real estate, according to Brooklyn-based food writer Ya Roo Yang, , who has written extensively on Asian cuisine for publications including the New York Times, Edible and Chow.

“If you want authentic at a reasonable price point, then it all has to do with the immigration pattern and real estate prices,” said Ya Roo Yang. “Most authentic Chinese food tends to cater towards the immigrant population (legal or otherwise) and they tend to live in the outer boroughs where the rent is cheap and there is already an established community.”

Inside these immigrant enclaves, like Sunset Park’s Eighth Avenue, Bensonhurst’s Avenue U and Sheepshead Bay along 86th Street and Bay Parkway, there’s plenty of great Chinese food.

But in parts of the borough with fewer Chinese residents, simple economics forces restauranteurs to make blander food.

“Outside of these communities, authentic Chinese food can’t gather enough customers to survive,” said Ya Roo Yang. “The restaurant owner must cater to everyone else, so Chinese food becomes diluted to have mass appeal.”

That said, detemining what’s “authentic” can be harder than choosing whether to order steamed dumplings or fried dumplings.

With more than a dozen discrete varieties from different parts of the country — not to mention Americanized versions of Chinese cuisine — it can be hard to define the difference between Chinese food and real Chinese food.

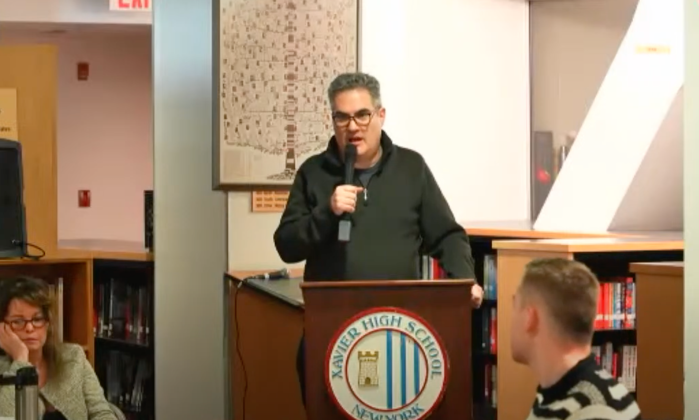

“There are dozens of types of Chinese food, and the most delicious items don’t appear on lists you often see,” said Jeff Yang, a columnist for the Wall Street Journal and media consultant for Iconoclast, a firm that targets Asian consumers. “There’s no General Tso’s Chicken — you can’t do that if you open that type of restaurant where the majority of the population is not only not from your part of China, but not from China at all.”He claims that the much-maligned Chinese eateries that are ubiquitous in brownstone Brooklyn would seem foreign if they were actually located in China.

“[That] weird mix of Sichuan, Hunan and American that you would never recognize in China; that Chinese food is as American as apple pie,” he said.

Many immigrants pursue the American dream by opening restaurants when they arrive in the country, but their children aren’t always interested in continuing the business.

“Second-generaton Chinese will be more educated than their parents who own a restaurant,” said John Jung, author of “Sweet and Sour: Life in Chinese Family Restaurants.” “They have college degrees, and maybe they grew up helping out in the restaurant but afterwards, they have better ways of earning a living.”

But the children of immigrant restauranteurs who do stay in the restaurant business might be Brownstone Brooklyn’s only hope, approaching Chinese cooking with a greater awareness of American food trends and a broader understanding — and willingness to challenge — the tastes of a borough-wide clientele.

Late last year, Melissa and Eric Har, both first-generation Americans born of Chinese immigrants, opened a Chinese restaurant on N. 6th Street in Williamsburg called The Wok Shop.

Melissa grew up in a Chinese restaurant her father owned in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where she worked as a clerk since the age of 14. In Williamsburg, though, she and her husband — who graduated from culinary school — are going in a different direction.

“We opened a Chinese restaurant because we wanted Chinese food and couldn’t find any outside of Chinatown,” Melissa said. “We want it to be better for you, healthier for you.”

“It isn’t authentic,” Eric added. “I come from an Italian cooking background. But it’s from my memories; it’s Chinese food through the lens of a Chinese-American.”