State Sen. Jabari Brisport is on the move, spending nine weeks talking with families and caregivers as he prepares to introduce a Universal Child Care bill in Albany’s upper chamber next year.

Brisport, who represents parts of Brooklyn including Fort Greene, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and Gowanus and chairs the senate’s Children and Families committee, announced in August that he would be introducing legislation to provide child care for all New Yorkers.

“It remains true today that women bear the brunt of child care responsibilities,” Brisport said in a speech announcing the legislation. “It remains true today that pressuring half the workforce into staying home is oppressive and deeply inefficient. And it remains true today that widespread access to employment is dependent on widespread access to child care.”

Before the legislative session begins in January, Brisport is traveling around the state to get feedback from those most affected by, and most knowledgeable about, access to quality child care and the lack thereof.

A report released earlier this year by the state’s Child Care Availability Task Force found that the average yearly cost of infant care in a child care center was more than $15,000. A smaller, family-based center was slightly less costly, at about $10,000 per year.

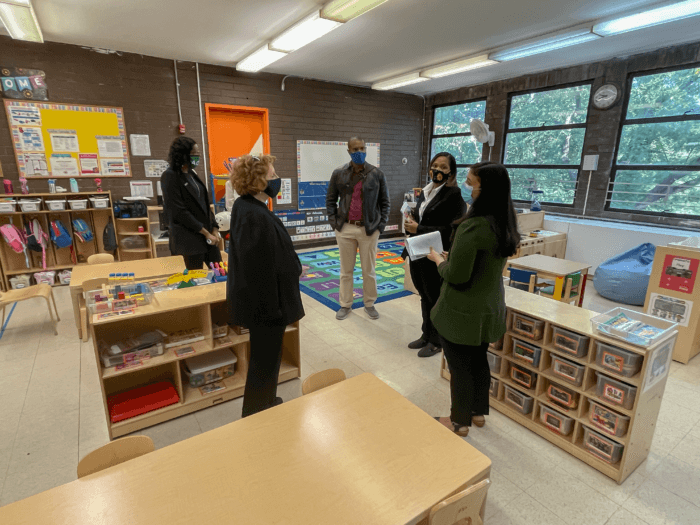

The listening tour, happening both in-person and in evening Zoom sessions, kicked off in Brooklyn last week as Brisport visited the Helen Owen Carey Child Development Center, an early-learning center in Park Slope run by the University Settlement House, and Greenpoint Garden Playhouse, a family child care center in Greenpoint.

Greenpoint Garden Playhouse offers after-school pickup for some young school-aged children and full-day care for two-year-olds. The center also provides a small number of free 3-K seats in affiliation with the Department of Education’s Universal 3-K program.

Kasia Kaim-Goncalves, GGP’s founder and director, said the center received 142 applications for five spots in the 3-K program. At least half of those applications were for extended-day or extended-year, she said, federally subsidized programs that provide care after school hours and on days DOE programs are closed.

“Definitely, it speaks to the need of expanding this program to more families,” Kaim-Goncalves said, during the virtual portion of the tour. “Because not everybody got a seat. And in this ZIP code where I’m in, 11222, we were the only provider of 3-K. Not a single public school offers it, not any other day care center. We are actually like a child care desert.”

3-K programs in the neighborhood are expensive, she said, and while some may say it’s the cost of living in New York City, families who have called the neighborhood home for years found costs rising around them.

“I’ve been in this neighborhood for a long time,” Kaim-Goncalves said. “That’s why I’m here. I couldn’t choose to be here now. I couldn’t choose not to be here at the moment. And there’s many families like mine who sort of found themselves in the middle of this situation where everything is so expensive, and one of the things that’s expensive is child care.”

The Task Force report said the state should work toward ensuring that no family pays more than 10 percent of their annual income on child care, and that low-income families pay not more than seven percent.

In 2019, Greenpoint and Williamsburg had an annual median income of more than $99,000, according to the Furman Center, higher than the citywide AMI of about $70,000. Under federal guidelines, 20 percent of the population was living below the poverty line — $26,500 for a family of four. According to city data, more than 40 percent of households were spending 35 percent or more of their annual income on rent.

Nora Moran, director of policy and advocacy at United Neighborhood Houses, said “center-based” care centers, like the Helen Owen Carey center, are seeing similar trends.

“When there are those subsidized seats open up, there is a lot of demand, a lot of family interest,” she said. “They do fill up quickly.”

There were only enough seats in center-based care facilities for 7 percent of babies born in 2015-2016 in Park Slope, Red Hook, and Carroll Gardens, according to a 2019 report from the city comptroller’s office.

While Park Slope might be seen as a wealthier neighborhood, Moran said, there are many families with lower incomes who are priced out of expensive child care options in the area.

Some parents and caregivers, she said, also prefer to have child care close to their workplace, rather than closer to home, something organizers and lawmakers should keep in mind as they work to improve access.

Lack of affordable, quality child care can keep caregivers out of the workforce. At least 87,000 people statewide were working part-time because of problems securing childcare, according to the Task Force report, and more than 5,000 were not working at all.

Additionally, Moran said, young children benefit from high-quality early education and socialization, especially if they’ve been cooped up inside with just their family members during the pandemic. Making sure that those kids have somewhere to go where they will be safe and supported is critical, she said.

Much of a Sept. 29 Zoom meeting focused on care out of the home, but Katy Cecen, a local midwife and lactation consultant, said parents should be given more options if they want to stay at home and take care of their young children.

“If we’re paying child care providers to take care of children zero to two, but there’s no option for people who want to take care of their own children primarily during that time, we’re essentially saying it’s work that’s worth being compensated for if somebody else is doing it,” Cecen said. “It’s only financially valuable to the state if somebody who’s not biologically or otherwise related to the child is providing the care.”

Cecen said giving the money that would be spent on child care directly to parents who may be choosing to stay at home was worth considering.

In his time in the senate, Brisport said, he’s seen a number of “tweaks” to child care policies, moving toward the goal of universal child care but never quite achieving it.

Child care amounts to “secondary rent,” for many families, he said, and even the less expensive options can be prohibitive.

“I think that paying a lot for child care is good, because that means that the providers are paid well, but in terms of the burden on parents — your typical working-class parents can’t do that,” Brisport told Brooklyn Paper.

A socialist, he thinks public services should be free at the point of service and is willing to fight to make that reality.

“It seemed almost like a perfect match that as a socialist who is chairing this committee, that we should be fighting for universal childcare,” he said. “Due to the nature of Albany politics in general and the previous governor, I think a lot of people felt it was out of reach.”