It’s the new Downtown Brooklyn Plan!

The city should let Downtown developers build taller towers in exchange for including artist studios, rehearsal rooms, and other dedicated artsy venues in their buildings, ensuring the area’s creative community isn’t pushed out by rising rents and new luxury apartment blocks, says a local business group.

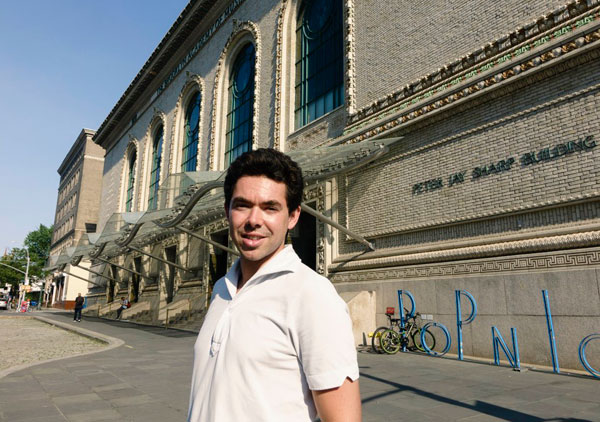

“The big shiny buildings have been built and all of the artists may be going away soon, so we need to create a sustainable cultural ecosystem to keep the area alive,” said Andrew Kalish, of the Downtown Brooklyn Partnership, which just announced the idea as part of a larger proposal for boosting the arts Downtown.

The city formed the Partnership a decade ago to encourage new business and development in the nabe after upzoning it in a scheme called the Downtown Brooklyn Plan, which ignited a boom of new residential and office buildings.

At the time, it also took control of developing the so-called Brooklyn Cultural District — a hub of theaters and arts organizations centered around the Brooklyn Academy of Music — which it claims has been a success, with the addition of new properties including the Polonsky Shakespeare Center theater, Bric House, and the still-rising BAM South, an apartment building that will also house a performing arts center and an art gallery.

But the organization says there is still a dearth of places for people to actually create art — rather than just present it — in the increasingly pricey nabe, so it wants the city to reward real-estate tycoons for creating them, just as it does for those that include public plazas or space for schools.

“If everybody gets on board, this is the mechanism that would work,” said Kalish. “There’s been plenty of zoning variances that have been created over the years.”

Area Council members Steve Levin (D–Downtown) and Laurie Cumbo (D–Fort Greene) are on board, but a city planning expert says it is unlikely Mayor DeBlasio or other pols would ever support rewriting the zoning code to favor artists, because it would open the door for any and every other special-interest group to make similar demands.

“When the government does something like that it creates a precedent,” said John Shapiro, who is the chair of planning and environment at Pratt Institute. “The idea of preferencing one population is a really tough argument, and however popular artists are in our culture, I think it would be hard.”

Shapiro said the partnership would have more luck appealing directly to developers, and trying to convince them that people will want to live in buildings where artists are working.

“Anything that developers can do to associate their development with the art district will help them with their marketing,” he said. “It’s perfectly conceivable that a developer could be persuaded to do this even if the city doesn’t do it legislatively.”

The Partnership’s plan also includes a raft of other ideas, among them:

• Reserving 10 percent of below-market-rate housing in the area for artists — although Kalish admits defining who is and isn’t an “artist” would be tricky — and running seminars so they know how to apply for it.

• Constructing new artist spaces on the vacant upper floors of the Brooklyn Bridge Park administrative building at Furman and Joralemon street.

• Funding more public artworks and performances around the neighborhood.

• Creating a neighborhood-wide arts festival a la Bushwick Open Studios.

The plan specifically focuses on Downtown, but Kalish said the proposal could serve as an example for other areas around the city.

“The plan could be easily blown up into something much larger,” he said. “As the city continues its larger cultural plan, we would hope this would serve as inspiration.”