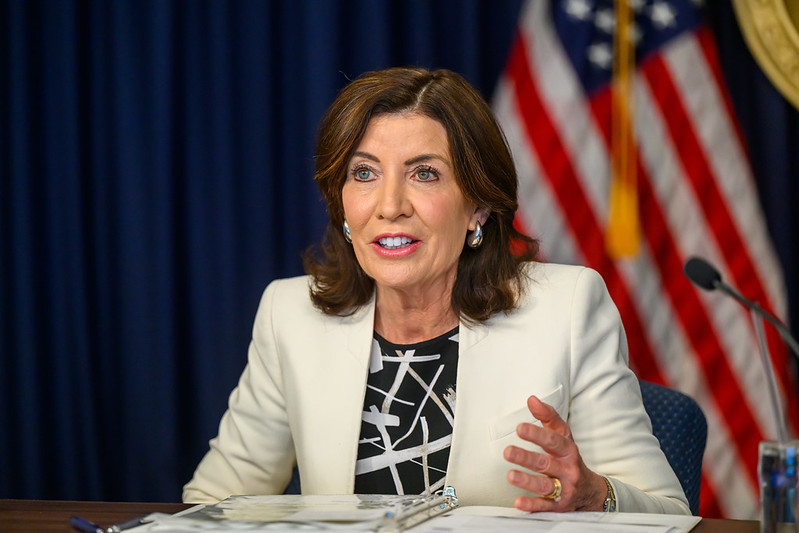

Park Slope native Hugh Carey, the two-term governor who helped pull New York from the brink of economic disaster in the 1970s, died on Sunday. He was 92.

Carey, who was labeled as a political maverick for running for the state’s highest office against the wishes of New York’s Democratic political machine — and then winning — passed away surrounded by family at his longtime summer home on Shelter Island, according to Gov. Cuomo’s office.

Brooklynites who remembered Carey’s many contributions during his 21-year political career were heartbroken by the news.

“[Carey] created a legacy that few other New Yorkers can claim,” said Sen. Charles Schumer, a Park Sloper himself.

Carey’s legacy began on Park Place near Sixth Avenue, just paces away from St. Augustine’s parochial and high school, which he attended.

The man who would be credited for saving New York from fiscal ruin in the 1970s grew up learning how economic calamities affect everyday citizens.

A child of the 1930s, he and his six brothers got a first-hand view of how the Great Depression nearly killed his father’s burgeoning oil distribution business, former state Sen. Seymour Lachman explained in his biography about Carey, “The Man Who Saved New York.”

Carey grew up in a embittered time when people distrusted government, Lachman explained.

In fact, in a knee-jerk reaction to the Depression, as well as World War II, which loomed in the distance, Carey and his fellow classmates at St. John’s University’s Brooklyn campus lashed out against their apparent lack of opportunities, forming the “Life Stinks Club,” he said.

“[It] was not a an organized fraternity, but a collective, cynical statement of sorts about what their prime years seemed to hold for them and their generation: a bad economy, military conflict and limited horizons,” Lachman wrote.

But Carey’s pessimistic outlook on life didn’t last long: after serving with distinction in World War II, Carey married, became an attorney, and, although he was never considered part of Brooklyn’s democratic machine, ran for Congress in 1960, besting a Republican incumbent on a pro-Catholic wave started by President John Kennedy.

In a district stretching from Park Slope to Bay Ridge, the seven-term congressman quickly rose in the ranks to become the chairman of the powerful Ways and Means Committee.

A staunch moderate, Carey managed to befriend most liberals by opposing the death penalty and by becoming the first Congressman to come out against the Vietnam War. He was also pro-Choice, although he became a strong pro-life advocate in the late 1980s, after he had retired from political life.

His 1974 candidacy for governor was wrought with setbacks — the first being the death of his wife Helen, who succumbed to cancer at the beginning of his campaign. Carey soldiered on, claiming that he promised his wife that he would continue.

But no one had rolled out the welcome mat for him: at the time, Brooklyn Democratic boss Meade Esposito told Carey that his “head would roll in the gutter” if he ran against the party’s candidate, businessman Howard Samuels. Esposito’s ultimatum only made Carey re-double his efforts, Lachman explained.

“The congressman liked the idea of running as a maverick Democrat, not beholden to the county leaders or their demands for jobs and laws and contracts from the victor,” Lachman said.

That September, Carey secured the Democratic nomination, defeating Samuels with 61 percent of the vote. Then, riding a pro-Democrat sweep following Watergate and President Nixon’s resignation, Carey defeated Republican incumbent Gov. Malcolm Wilson, getting 57 percent of the vote.

Yet he may have wished he hadn’t: at the time, New York was in shambles — and was about to fall into an economic abyss.

Carey quickly rose to the occasion: during his inaugural address, he set the tone of his freshman term, explaining that “This government will begin today the painful, difficult, imperative process of learning to live within its means.”

He spent his first year in office creating agencies that gave him unfettered power over city and state finances, allowing him to reject all budgets and labor contracts and remove long-standing entitlement programs. Once he had wrangled control of the state’s finances, he reached out to both business and labor — getting banks to refinance the city’s debt and unions to invest their pensions into its coffers.

Carey did all of this without the help of the federal government. At the time, President Ford had promised to veto any bailout bill for New York (a pledge that led to the famous, though somewhat inaccurate, New York Daily News headline: “Ford to City: Drop Dead!”).

After a year in office, Carey had righted New York’s fiscal ship enough to impress Ford, who approved $2.3 billion in federal loan guarantees — pulling New York off the financial cliff it had teetered upon.

Borough President Markowitz, who had served three years under Carey when he was state senator, said Carey learned the tough-guy skills to save the state from the streets of Park Slope.

“Governor Carey used that ‘Brooklyn attitude’ to achieve so much during his storied political career — including saving New York City from financial ruin and helping to promote economic development in Brooklyn and the other boroughs outside of Manhattan,” Markowitz said in a statement. “I hope [his family] will be comforted by the thoughts and prayers of millions of New Yorkers grateful for his service.”

Carey is survived by 11 of his 14 children; 25 grandchildren; and six great grandchildren.