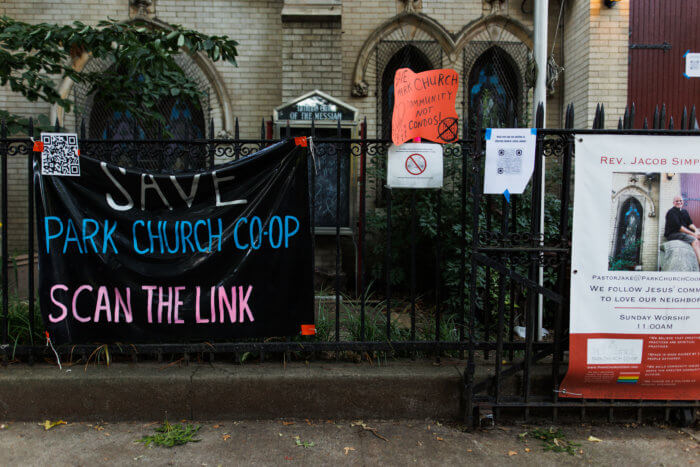

On Thursday, June 30, about a dozen people were gathered on the steps of Park Church Co-Op in Greenpoint. It was the church’s last ever day of operation, and congregants and supporters were discussing next steps as they fight to, somehow, keep the church and its community alive.

“There’s a lot of people who come through this space and meet the community without having any connection to the religious part of it at all and that’s because when it was the Park Church, its mission was to love your neighbor,” said Jamie Hook, who helped organize the rally.

“And that’s the mission upon which I think we can legitimately say, ‘Hey, whoa, selling it for $4.5 million to someone who’s going to knock it down is not honoring the mission.’”

The nearly 125-year-old Lutheran church, which reopened as Park Church Co-op after a brief closure in 2015, has long struggled financially — but a 2020 infusion of cash from its governing body, the Metropolitan New York Synod, seemed like a shot at a new life.

The Synod promised a new pastor and five years of slowly-decreasing financial assistance as the church found its footing. A little over a year later, the Synod announced they’d be reducing their monetary contributions early — then stopping them altogether, forcing the church to close.

Online petitions, fundraisers, and letter-writing campaigns proved fruitless. In April, the Russell Street building was listed for sale for $4.5 million.

“I’m not a congregant,” Hook said. “I’m arguably kind of allergic to religion. And yet this church has woven its way through my life in so many ways.”

A day-long celebration with live music and plenty of food brought the church’s busy life to a bittersweet conclusion on June 18.

Pastor Jacob Simpson, who was sent to the church in the summer of 2020, delivered his last sermon the next day. Programs that operated inside the church, like music lessons and a Pre-K, were allowed to continue until last Thursday.

The last few years at Park Church Co-Op

“The Synod’s communication with their congregation has been really poor,” said Concetta Abbate, a longtime congregant and music teacher at the church. “They’ve made a lot of internal decisions that were not communicated. There was one person in the Synod who said, ‘We’re still deciding,’ and they had really, internally, already made the decision to not just close the building, but also close the community congregation.”

Money and the size of the congregation have long been issues at Park Church, but the small number of people regularly attending services at the church — about 35, as of last December — wasn’t the only metric of success for congregants.

The church partnered with local organizations, offering up their physical space for programming. On weekdays, the church was bustling with preschool students, music and art classes. On the coldest winter nights, the congregation partnered with a local nonprofit to provide shelter for homeless people who had been sleeping outdoors in the neighborhood. Local bands often performed in the church or on its front steps, across from McGolrick Park.

Abbate found out that the building had been listed for sale when she spotted real estate agents walking through the church while she was teaching a music class, she said.

Since last year, the Synod has been encouraging Park Church to host more fundraisers and charge their commercial tenants higher rents, she said, seeming to promise that enough money raised could save the church.

Park Church had always collected the rent from its tenants directly, but in January, that changed — the Synod announced it would be stepping in to collect the rents directly, a person with knowledge of the situation who asked to remain anonymous said.

“We realized that no amount of money was going to stop the church from closing, and from them selling the building,” Abbate said. “So, now we’re in this situation where several people have given thousands of dollars and thousands of hours of their free volunteer labor. And nobody’s getting any kind of reparation or compensation for all of this unpaid work put into something that was set up for failure behind the scenes.”

In October 2021, the Synod Council voted unanimously to end financial support for Park Church Co-Op by the end of the fiscal year, according to meeting minutes.

“The well-being of our congregations and their members is a top priority for me and my staff, and in today’s increasingly secular society, a matter which we deal with daily,” said Bishop Paul Egensteiner in a statement to Brooklyn Paper.

The church’s predecessor, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Messiah, closed due to financial hardship in 2015. But, with a grant from the Synod, then-pastor Amy Kienzle was able to open its doors again, this time as Park Church Co-Op.

“I’m disappointed in the decisions that were made since they were out of our control,” Simpson said. “I wanted to stay here and so did the congregation. Nevertheless, I love the people at Park and the people of Greenpoint, and will be forever grateful for by two years here.”

Synod claims missed development benchmarks

Since that time, the church has been operating as a “Synodically-Authorized Worshipping Community,” Egensteiner said, and, as such, had entered an agreement to meet certain metrics on its way to becoming a self-sustaining, independent church.

“During the time of Park Church Co-op’s establishment, the community’s growth stagnated and consistently missed the required benchmarks in development; as a result — and after much difficult deliberation — our Synod Council voted to cease funding for the site,” Egensteiner said. “This decision was not taken lightly and actions such as this are only sought as a very last resort. Thus, given numerous factors, the greatest of which is the dire structural integrity of the building, we can no longer justify funding the Park Church Co-op while so many other congregations in our Synod are in greater need of support.”

In late December, as the clock ran out on funding, the Park Church “core team” sent a letter to the Synod council, asking them to reconsider their decision to close the church given the community’s “deep desire” to remain open.

A brief response from Renée Wicklund, the Synod’s vice president, read: “This letter was considered at the regular meeting of the synod council on January 18, 2022. The synod declined to take additional action; as such, its prior decision stands.”

In a February 2022 letter, the core team asked for more details on which benchmarks they had missed, telling the council they felt the church “on a solid path to financial independence,” having secured long-term partners and grown the “worshiping community.”

On March 7, Wicklund responded in a letter to the core team and Simpson. She explained that in an October 2019 meeting, the church’s leadership team had promised to reach financial independence within one year. After that, the Synod would cease financial assistance but would retain control of the church.

At the time of the meeting, Park Church was operating without a pastor — Kienzle had departed months earlier, and Simpson would not arrive until the next year.

In the spring of 2020, just after Simpson was sent to Park Church, the Synod realized the congregation was not ready for financial independence, and placed it on the five-year “step down” plan. Then came the October 2021 vote to end all financial assistance.

“To date, our Synod has invested more than $800,000 in the attempt to make PCC a viable ministry,” Wicklund wrote. “Continued financial support does not fit within the Bishop’s well-defined plan for our synod’s future, 2025 Vision.”

Communication lags, and the local politicians step in

The commotion caught the attention of the neighborhood’s local elected officials — councilmember Lincoln Restler, Assemblymember Emily Gallagher, and state Senator Julia Salazar.

On June 7, the trio sent a letter to Egensteiner and the charities bureau of the state Attorney General’s office. According to state law, the AG must approve the sale of the church before it can be finalized.

“We ask you to pause this sale and come to the table to explore other options,” the pols said. “Our doors are open to collaborative conversation that meets everyone’s needs.”

Gallagher’s office has had some conversations with the Synod, according to a staffer, and have discussed the possibility of helping to organize a community-based nonprofit who could purchase the building and keep it open as a community center — but the most promising option, short term, is getting the body to agree to delay the sale of the building.

Last week, the Friends of Park Church Co-Op updated an online petition that originally sought to keep the church open. The group now intends to file a complaint with the AG, alleging that the sale of the Synod would violate state law, and will send the nearly 3,000 supportive signatures along with it.

“We know that there is a very slim chance that this complaint will receive the notice that we feel it deserves, but in the absence of any other action to preserve this building for community use, we feel we must take this action,” wrote Mike Nowatarski, a congregant and member of Friends of Park Church.

Park Church Co-Op is “deeply rooted and connected to all things Greenpoint,” Restler told Brooklyn Paper, opening its doors to all kinds of community events.

“They have demonstrated zero interest in engaging with elected officials or community leaders from Greenpoint in our efforts to save the beloved Park Church Co-Op,” he said. “I am just livid that the Synod seems to only be focused on its bottom line and not the incredibly strong community that has sustained Park Church over the years.”

Restler has called the Synod and reached out in writing multiple times, he said, and his office will continue to try to make contact, but he has never gotten a response.

“They’re not interested in speaking to us or hearing from our community. They just want to make as much money as they can,” he said.

Several Lutheran churches in the Bronx and Staten Island have been closed by the Synod and sold off in recent years, despite widespread community support.

Losing trust in the church

It was hard to fundraise in the church’s last few months knowing that all the money in its coffers would be headed right to the Synod after June 30, Abbate said. She decided not to raise money for the farewell party on June 18, instead encouraging attendees to tip the musicians directly and bring food for a potluck.

The Synod has referred Park’s congregants to other nearby Lutheran churches, like St. John’s Lutheran Church a few miles away or St. Paul’s in Williamsburg.

“There’s definitely a consolidation of resources and the idea that people should just go worship at St. John’s,” Abbate said. “But we all know that that’s not how organic community works. It’s a different culture, it’s a different group of people.”

Churchgoers had looked for alternative spaces to continue services, but, even if one was found and weekly meetings started, it wouldn’t quite be the same.

“I was talking to our church pianist and he was like, yeah, I think I need a break from church for a while,’” Abbate said. “I was just like, yeah, I get that. I’m not really super enthusiastic about joining a church. This experience has been pretty awful.”

Hook, who organized the rally on the church’s final day, said there’s a “snowball’s chance in Hell” that the appeal to the AG will work, but it’s a chance worth taking.

Alice Cohen, who also attended the rally last week, agreed. She’s Jewish, and has never attended religious services at the church, but has been attending concerts and community events on Russell Street since the 90s.

As he prepared for his final sermon, Simpson, who was planning a series on the Ten Commandments, said he was focusing on one most important verse in Matthew: “He said to him, ‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the greatest and first commandment. And a second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets.”

“People always forget the second part of what Jesus says, ‘On this rests the law and the prophets,’” Simpson said. “My interpretation has always been, you can interpret all the rules, all the laws, all the ordinances of scripture, but it all comes back to how we love each other and treat each other. That’s like, the foundation of my personal theology.”

Additional reporting by Paul Frangipane