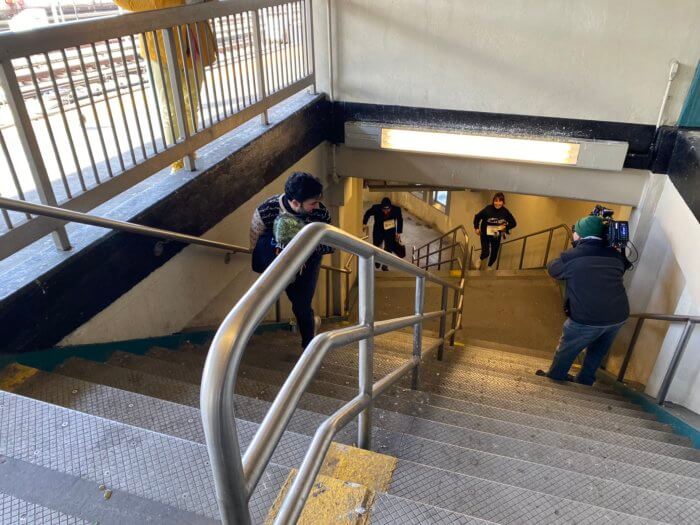

A row of eager commuters lined up in front of the turnstiles at the Smith-9th Streets subway station in Gowanus on Friday, MetroCards at the ready, and began sprinting up the stairs to the platform of the city’s tallest subway station.

It’s not an unusual sight — thousands of commuters board and exit trains at the station each day — but these riders were trying to make a point: that an underfunded MTA and long wait times have a huge impact on their constituents, and something needs to be done. With their tennis shoes tied tightly and race numbers on, four local elected officials were racing each other to the top to recreate the mad dash straphangers make each day to catch a train rather than wait 15 or 20 minutes for the next one.

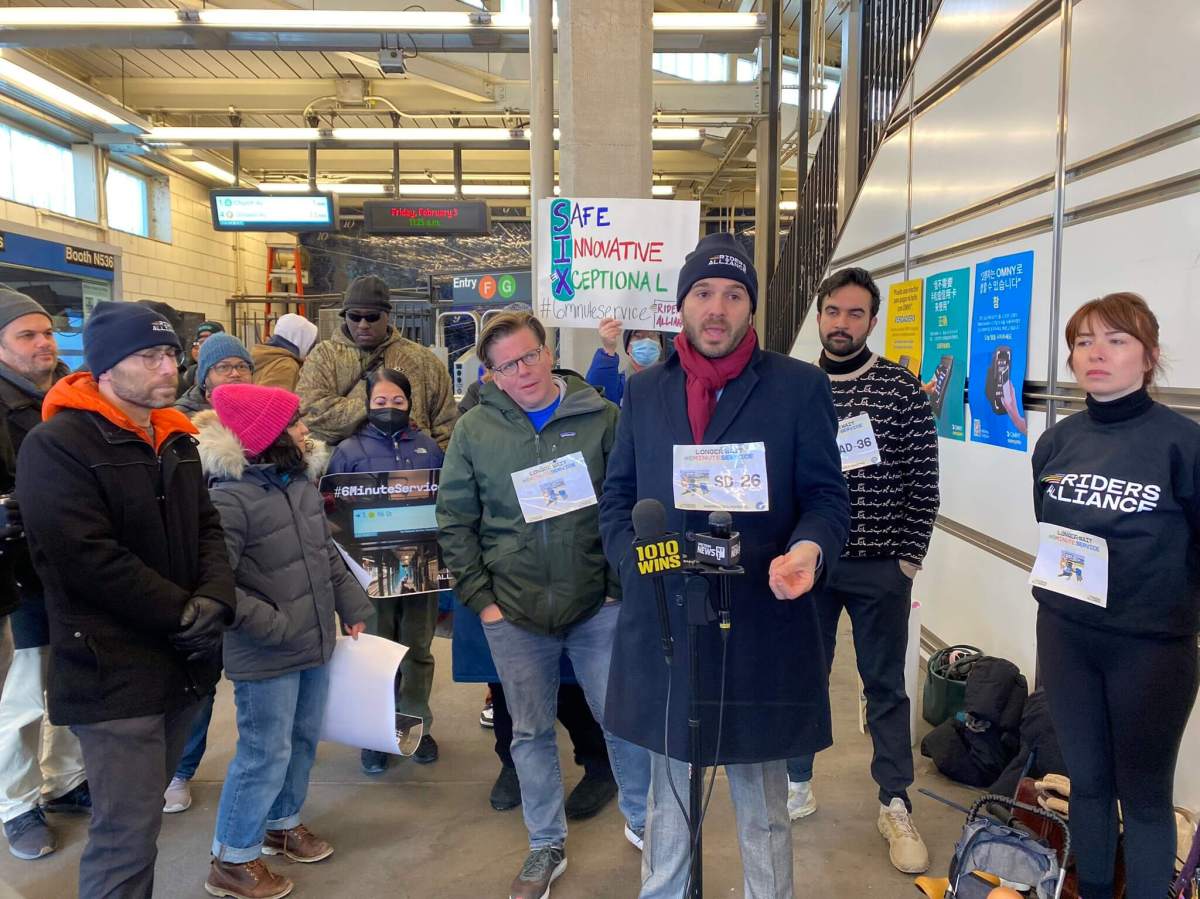

For years, advocates have pushed a for six-minute wait times on all lines, at all times. To do that, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority needs more money.

In her preliminary budget plan, released Feb. 1, Gov. Kathy Hochul proposed several measures that would help the MTA bridge its $3 billion budget deficit, including calling on New York City to pay out an additional $500 million to the beleaguered agency. Even then, the MTA would be operating over $1 billion short.

“We heard earlier this week that the governor has a rescue plan for the MTA, just to maintain bus and train service that we have today,” said Danny Pearlstein, Policy and Communications director at Riders Alliance, a group focused on improving public transit in the city. “We need more state revenue, because fares aren’t bringing in that much money. But we also need to expand service because we need to bring more riders into the system, that would bring more revenue.”

Late last year, a panel created by Hochul and New York City Mayor Eric Adams released a report called “Making New York Work For Everyone.” The panel recommended improving off-peak frequency and reliability as part of a larger plan to encourage more people to ride public transportation.

While ridership is lower during off-peak hours, the report notes, those trains are a lifeline for people who work outside the usual 9-5, including healthcare and hospitality workers and delivery drivers.

At about 11am on Friday morning, as the pols prepped for their race, the next Church-Avenue bound G train was still 11 minutes away, and temperatures were hovering in the low 20s. On weekends, many riders wait 12-20 minutes for a scheduled train — and delays and service suspensions often make the wait even longer.

State senator Andrew Gounardes, who represents the nabe in Albany, said the Smith-9th Streets station is a “hub” for people who live in the area, especially in transit-strapped Red Hook. Every day, people sprint to the platform just to watch their train pull away.

“That’s not the way to have a functioning public transit system,” Gounardes said. “We have to radically rethink how we fund public transit using public dollars. We should not have a public transit system that is funded on the backs of riders.”

Late last year, the MTA released its own agency-wide proposed budget, and it was rife with cost cutting measures – including possible fare hikes that would bring subway and bus costs above $3 for the first time.

Gounardes and his fellow runners — assemblymembers Jo Anne Simon and Robert Carroll, of Brooklyn, and Zohran Mamdani of Queens — are hoping Hochul and their colleagues in Albany will dedicate enough state funding to fully fund the agency.

“I’m glad that the governor has proposed the investments she has, but, as Andrew said, it’s not enough,” Simon said. “It is really critically important to the lifeblood of our city and our economy for people to be able to take reliable, safe, regular, speedy-enough transit service. That’s what’s going to get people out of their cars.”

Both the state and the city are working to massively reduce their carbon emissions in the coming decades – and getting more people on trains and buses is a critical part of that plan. In 2020, gas and diesel-powered on-road vehicles belched out more than 11 million metric tons of greenhouse gasses, according to city data.

The city hopes to reduce vehicle traffic and increase revenue for the MTA by implementing congestion pricing, which advocates say would push drivers to take public transportation instead. Hochul has hesitated to embrace the plan — but Carroll said it’s necessary to bring needed revenue to the MTA and bring riders back.

“We desperately need to make sure that we are fully funding the MTA, because if we do not have consistent and reliable service, this entire system could go into a death spiral where more and more people decide to opt-out,” he said. “We can bring back that ridership … [by] fully implementing congestion pricing this year. We took a hard vote in 2019 to get this done, this governor cannot rip that from us.”

The four participants — Gounardes, Carroll, Mamdani, and one of Simon’s staffers, filling in for Simon herself — took the race to the next level by loading themselves up with grocery bags, backpacks, and even a little stroller with a baby doll to recreate the conditions of an actual commute.

They weaved through straphangers on the stairs and escalators, leaving a trail of confusion and dropped produce in their wake. Mamdani took first place, with Gounardes at a self-described “close second.”

A one-time cash infusion isn’t a panacea for the MTA’s issues — the agency is reportedly on-track to run out of federal funds by 2024, and doesn’t have a clear source for additional cash beyond fares.

Gounardes said he and his colleagues are working on longer-term fixes in the statehouse with an in-progress package called “Fix the MTA.”

“Right now, the budget is primarily made up of rider revenues, and that’s not sustainable,” Gounardes said. “So we’re looking at additional funding sources … with a budget of $227 billion for the state, that’s a lot of money, there’s no reason why we can’t put an additional $300-400 million into this system.”