A southern Brooklyn lawmaker and a coalition of residents are bringing the city’s Department of Transportation to court in hopes of halting the conversion of a stretch of Seventh and Eighth Avenues into one-way streets — claiming that the city hasn’t done enough outreach.

“[The New York City Department of Transportation] are just bypassing the whole system,” said Assemblymember Peter Abbate, who represents a swath of southern Brooklyn which includes Sunset Park, Dyker Heights and parts of Bensonhurst. “They are just doing what they want to do and that’s not what city agencies are for.”

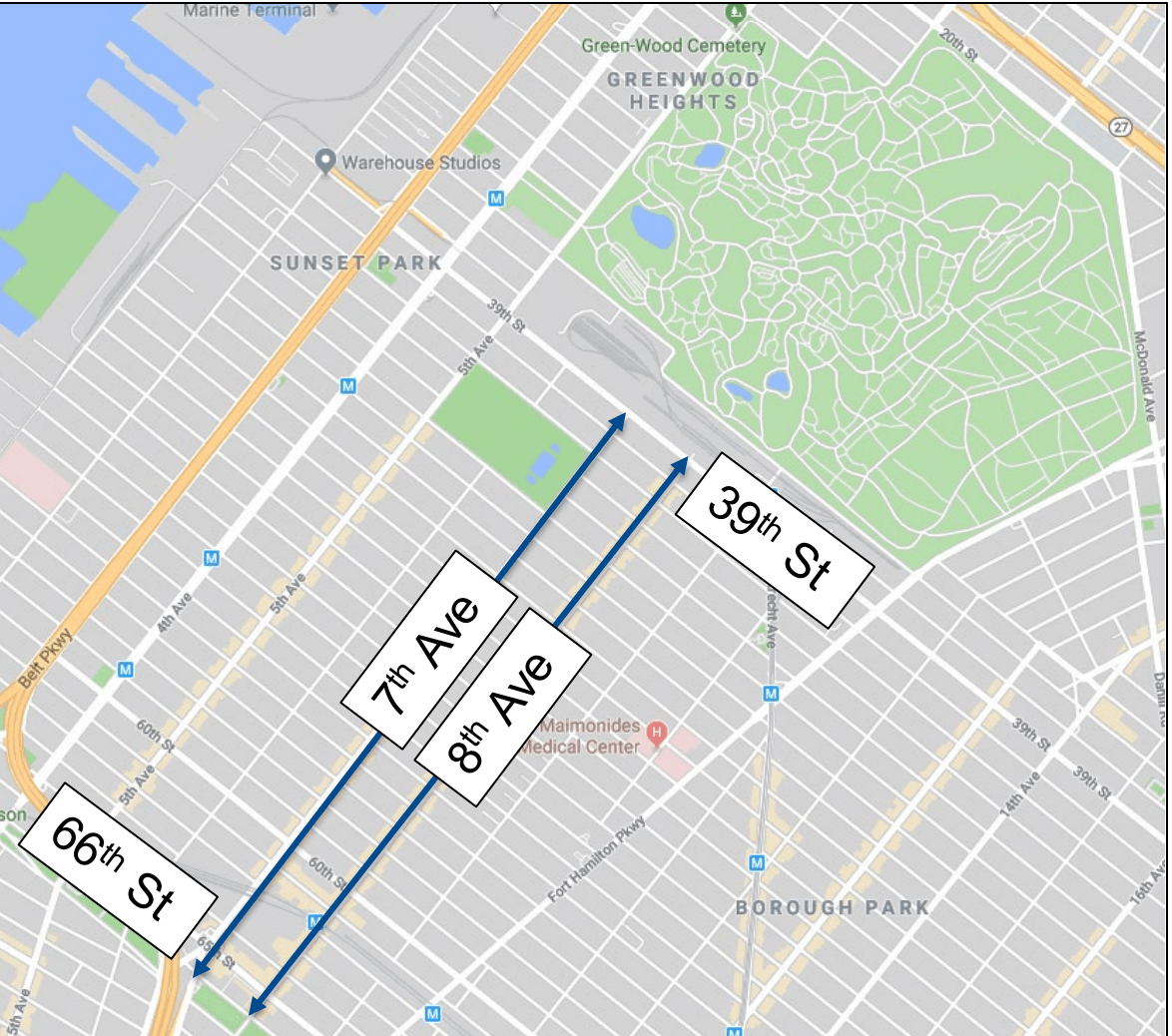

Under the DOT’s proposal, a portion of both two-way thoroughfares would be converted to one-ways, with Seventh Avenue running south between 39th and 65th streets, and Eighth Avenue running north over the same stretch. The project, which also includes new protected bike lanes, extended sidewalks and other safety configurations, spans community boards 7, 10 and 12.

The plan lies largely in Sunset Park, where the conversion will run through the heart of Brooklyn’s Chinatown — prompting backlash from members of the Asian community who have rallied against the proposal, claiming the conversion will destroy their commerce. Though, the new one-way streets would also run through a couple of blocks of Bay Ridge and Dyker Heights.

‘A paid posse of youngsters’

The nine plaintiffs — who, along with Abbate, include locals Kenny Guan, Bao Zhi Liu, Vincent Lu, Qinwen Lu, Paul Mak, Grace Mo, Kam Fon Mui and Tsang Sun Mai — filed an Article 78 proceeding, an appeal of a New York agency’s decision to the state courts, on July 7 alleging that the DOT knowingly violated the New York City Administrative Code when bypassing the mandated public outreach to the affected community boards.

That code requires the agency to notify the community board by email when there is any major traffic proposal comprising more than four blocks, after which the agency must bring the plan before the board upon the panel’s request, within 30 days of that request.

Instead, city transit bigwigs presented the project to a Community Advisory Board of which, the filing argues, members were handpicked to streamline the project, instead of including the impacted people and businesses.

“At the very least the people and businesses of the affected districts have a right to expect their voices to be heard through the legal processes set by the law,” the complaint states, “and not by a paid posse of youngsters, potentially skewing personal interviews to impress their superiors by obtaining the results desired by DOT to accomplish its ends.”

The filing further alleges that Bay Ridge Community Board 10 District Manager Josephine Beckmann requested in a May 3 call to DOT rep Leroy Branch that the agency provide a joint meeting for the three community boards, as well as a separate meeting for each board, as she similarly told Brooklyn Paper in June.

The filing states that Branch told Beckmann in response, “because DOT wanted this plan implemented by August, 2021, DOT was going to create its own public review process, thus bypassing the legally mandated Community Board process and the Community Board public hearing.”

Then, less than two weeks later, Branch allegedly emailed Beckmann requesting she join the Community Advisory Board to represent the views of CB10 — a process she’d never heard of prior to its use in this project, the petition alleges.

In neighboring CB7, District Manager Jeremy Laufer wrote to DOT Commissioner Hank Gutman on June 3, asking that he halt all conversion plans and end conversation with the “unprecedented and arbitrary ‘community engagement’ processes” until they work with the three respective boards, as is required in the City Charter.

The court filing also calls for the Kings County Supreme Court to prohibit the agency from commencing construction on the thoroughfares until the court makes a final determination, and to prohibit the use of the term “Community Advisory Board” in connection with the project.

A stressful situation

Though agencies like DOT have historically gone through the city’s community boards for feedback (their recommendations, at the end of the day, are purely advisory), many argue that the panels’ involvement often serves as a roadblock for safer streets.

And while the Seventh and Eighth Avenue conversion plan hasn’t gone board to board, the head of a southern Brooklyn-based bicycle advocacy group maintains that there’s been plenty of outreach.

“I haven’t perceived a lack of outreach,” said Brian Hedden, president of Bike South Brooklyn. “I have sat in on a couple of meetings and I know that they’ve had other meetings that I did not take part in. It does seem to me like the DOT has created a number of avenues where people can sit in on DOT presentations and have their feedback heard.”

In those meetings — held virtually amid the coronavirus pandemic — Hedden said DOT representatives made sure to address every comment in the chat and answer all relevant questions.

Hedden further argued that the conversion wouldn’t just benefit bicyclists and pedestrians who he said find traveling the thoroughfares chaotic but it would also provide smoother travel for vehicles and riders of the B70 bus.

“The whole thing is a high-stress environment and makes people not want to be there,” Hedden said. “In addition to actually increasing safety, it would also lower the perceived stress for anyone using that corridor … and hopefully make it accessible to larger groups of people.”

Similarly, a press representative for DOT said the agency has engaged residents of Sunset Park on several occasions about the plan to improve safety on the corridor, where the injury rate for children and seniors is 40 percent higher than the borough average — namely at two recent public forums where DOT answered over 100 questions.

“Seventh and Eighth Avenues are major Vision Zero priorities, and DOT has engaged Sunset Park in several conversations, across languages, on our plan to make it safer,” said Lolita Avila. “We’re looking forward to continuing those conversations and designing a plan that works for the community and keeps people safe.”

In the meantime, the project has been on hold since the lawsuit was filed in the Kings County Supreme Court on July 7 by Stephen Harrison, a lawyer and member of Community Board 10. The case will next go before Judge Rosemarie Montalbano on July 22, when the defense will attempt to compel the courts to allow the project to move forward while the lawsuit is underway.