Almost a year after the federal Environmental Protection Agency dubbed the Meeker Avenue Plume a federal Superfund site, the agency is working to determine the size and impact of the site as it takes its first steps toward cleaning up.

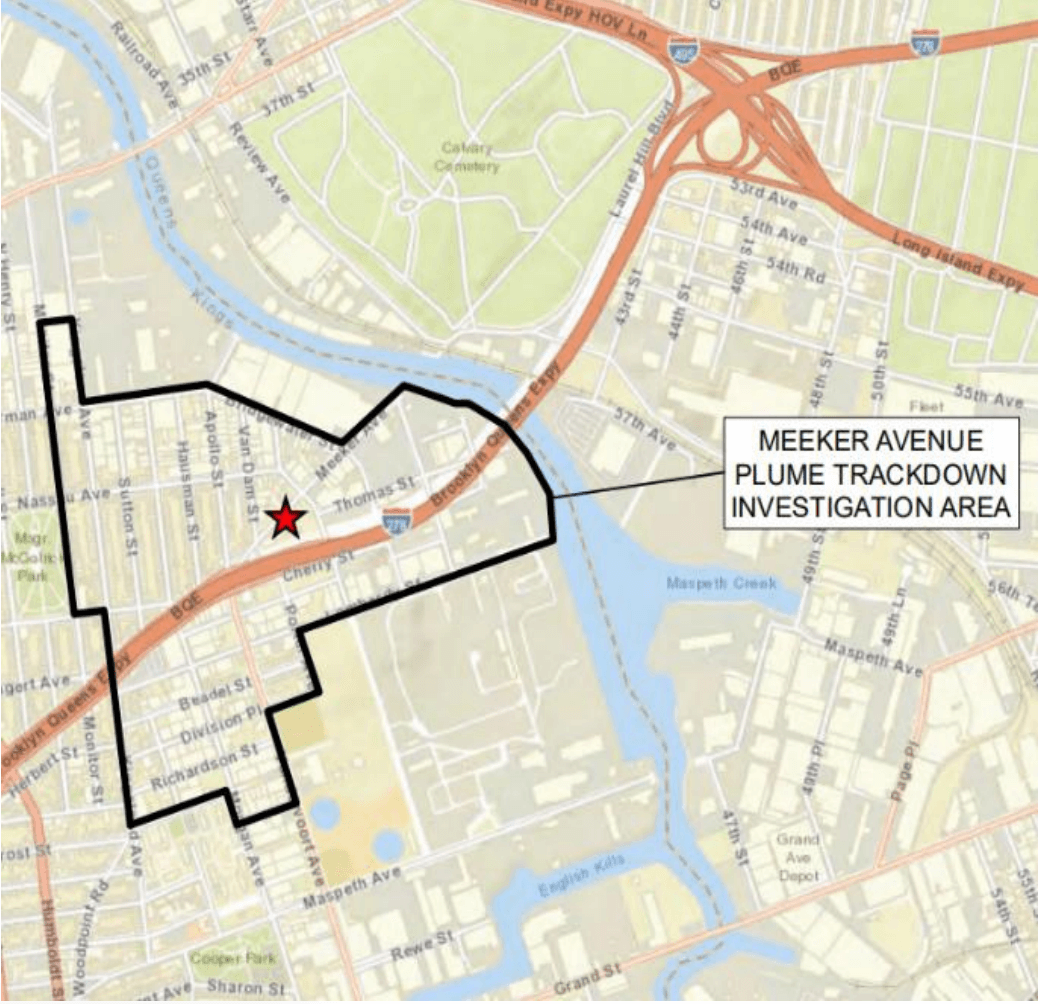

Superfund sites are nothing new in Brooklyn — the Plume is the most recent of four located within just a few square miles of each other in the borough — but it is unique in its scale. Contaminated soil and groundwater spread across about 50 blocks in Greenpoint, below streets, homes, and businesses.

Dozens of Greenpointers piled into the Greenpoint Public Library on Tuesday evening to get updates from the EPA and ask their many questions. Of particular concern to the EPA, the state, and residents is soil-vapor intrusion, when hazardous chemicals seep into buildings from the soil below.

Testing, mitigation, and worries

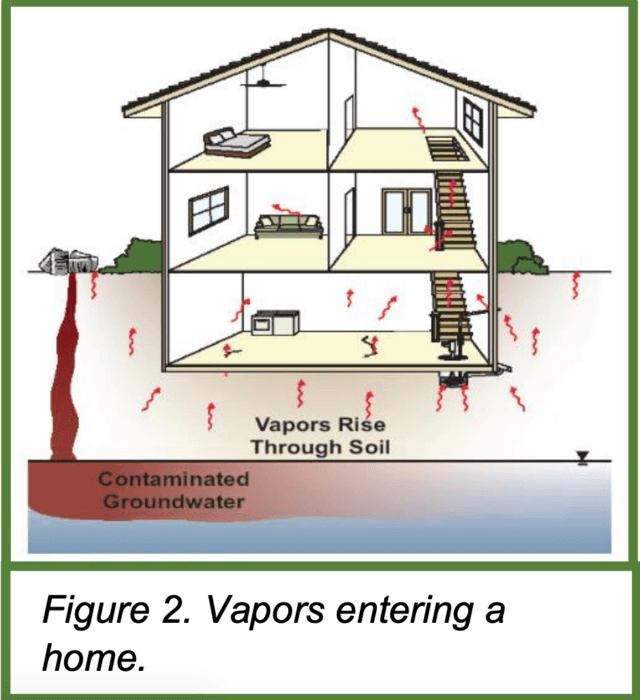

Since last fall, the EPA has mailed letters to at least 500 residents requesting access to their homes for testing — when given permission, the agency simply installs air quality monitoring equipment in the basement floor, where dangerous vapors like Chlorinated Volatile Organic Compounds are most likely to build up.

The benefits are two-fold. For one, the results, positive or negative, help the EPA to determine the boundaries of the Plume. If the air in a home or building is found to contain CVOCs — which can cause short and long-term health effects, including cancer – the EPA will install a pressurization system to keep the fumes out for free, keeping tenants and visitors safe.

Acceptable levels of potentially-dangerous chemicals are set to protect the most vulnerable people — young children or pregnant people, a health department rep said. Even if the indoor air is clean but there’s a buildup of vapors beneath the building, a mitigation system might be installed.

“If we find an issue in a building with a common space – let’s say the basement is used for laundry or something – we would make sure that any potentially-impacted residents are aware,” said Scarlett McLaughlin, a public health specialist in charge of hazardous site investigation for the state health department. “If we need to install a mitigation system and it’s a six-story building or a small townhouse, everyone in the townhouse will be aware that that is happening.”

Three structures were tested last November, according to an EPA spox, with additional tests scheduled for this coming March. Results take about three months, and will be shared directly with the owner — and eventually, the public, though the identifying information will be removed in the report. So far, no results have been reported from the November tests.

In March, the EPA will keep contacting home and business owners within the Plume to test the air inside their buildings, said John Brennan, EPA Remedial Project Manager. Indoor air-quality tests will continue during “heat season,” about November-March, for the next few years, and Brannan encouraged locals to reach out to the EPA to request testing if they live in or around the Plume.

Some concerned tenants have already hit roadblocks when it comes to testing, though. Roughly 85% of people in Community District 1, which includes Williamsburg and Greenpoint, are renters — who can’t ask for or approve testing directly. And not all landlords want to cooperate.

“What sort of approval is needed from landlords to get the testing done, and [is] there ever work done with tenants to negotiate access if the landlord is unwilling and unavailable?” one local asked.

The owner has to sign and approve consent for the testing, Brennan said. If a landlord is resistant, he suggested tenants reach out to the EPA directly, and they would contact the landlord.

Heidi Vanderlee told Brooklyn Paper she has already experienced some friction with her landlord after contacting the EPA for testing. She worries many tenants will hold back for fear of retaliation — and that those buildings won’t get tested at all, leaving residents at risk.

“There’s no real reason for them to do it if they’re not someone who cares about their building and the people in it,” Vanderlee said. “The EPA can’t compel them to do it … I wish there was some sort of legislation that would give the EPA more teeth.”

Identifying risks in public spaces

There’s more to be done outside of privately-owned homes and businesses, too. CVOCs and vinyl chloride, another chemical found in the Plume, are known to cause everything from damage to immune and reproductive systems to cancers.

Cooper Park Houses, a NYCHA public housing development, sits just south of the boundary of the Plume — and residents there say they’re already feeling the impacts of overlapping environmental hazards in the nabe. The EPA has a meeting set with NYCHA to discuss testing in the complex, Brennan said.

The EPA will also be testing public spaces — schools, including P.S. 110 and McGolrick Park, which sits right on the edge of the Plume — for contamination.

P.S. 110 was tested by the Department of Education in 2008, Brennan said, and “no further action” was recommended, indicating that it was safe — but that wasn’t enough for some parents.

Matt Williams has lived in the nabe for 12 years, and his nine-year-old son attends P.S. 110 and eats lunch every day in the basement cafeteria.

“I would think that testing would be ongoing,” he said. “It’s like, 2008, that was 14 years ago. Things change.”

Vapors can enter basements through cracks in the foundation, floors, or walls, according to the EPA, and Williams worried that while things may have been airtight in 2008, cracks could have formed in the meantime — posing a danger to his son and the other students.

“We used to live on Kingsland [Avenue,] which was in the original site … and then they broadened it to include P.S. 110,” Williams said.

Brennan was hesitant to make broad generalizations about how the chemicals could impact the health of residents – it depends on which chemicals are found in which areas, how bad contamination of indoor air is, and who’s exposed — young people, seniors, or people with pre-existing conditions could all be affected differently.

As for the map — the exact boundaries of the site are not set in stone. Rough guidelines have been established by years of previous testing by state and federal agencies, but groundwater testing will help the EPA find the sources of contamination, and just how far it’s spread.

What comes next for the Meeker Avenue Plume

With so much work already done, the experts have still barely scratched the surface of the Plume. Ten years passed before work started on the Gowanus Canal after it was added to the Superfund list, and a cleanup plan for Newtown Creek, just north of the Plume, isn’t expected to be completed until 2028, which was added the same year.

After all the testing is done, there will still be analyses and plans to be made. The EPA will hopefully name Potentially Responsible Parties — private companies who contributed to the toxic mess — who will be forced to help pay for the cleanup. A number of companies and sources have already been ID’d by the state.

The agency will also put together a Community Advisory Group — a collection of local residents and organizations who will work together with the EPA to spread information and make decisions about potential actions. A number of people have already reached out, said Community Involvement Coordinator Donette Samuel, and all are welcome.

Lisa Bloodgood, director of Horticulture and Stewardship at the North Brooklyn Parks Alliance and former Director of Advocacy and Education at the Newtown Creek Alliance, said she was glad to see a high turnout at the meeting — but she worried that not many landlords or business owners were present, when they’re the ones who will need to approve testing.

“I’m hopeful that it’s the beginning of a very long process, and I always am so grateful for how this community has worked together for so many years on so many really complicated problems,” she said.

While the process is sure to be long, there are some big differences between the Plume and the other Brooklyn Superfunds — namely, the chance to address immediate health concerns here and now.

“If you let the EPA in now, and there’s a risk in your home or your business, you can have that addressed and mitigated very, very quickly,” Bloodgood said. “You don’t see that at the other Superfunds in New York City where it’s all a longterm process.”

For more information or to ask questions about the Meeker Avenue Plume contact Community Involvement Coordinator Donette Samuel at (212) 637-3570 or at Samuel.Donette@epa.gov.