A new artist has been selected by the city to create the public art portion of Downtown Brooklyn’s long-in-the-works Abolitionist Place park. Incorporated in the new plans is a monument to abolitionist “conductors” who helped people escape slavery through the Underground Railroad.

Brooklyn-based multimedia artist Kenseth Armstead will take over from artist Kameelah Janan Rasheed after Rasheed and the city “mutually agreed” to part ways on the project, a rep for the Department of Cultural Affairs told Brownstoner. The spokesperson said the department thanks her for the time and energy she invested in the project.

The rep provided a statement from Rasheed saying: “I’ve made the decision to withdraw from the process of creating a public artwork for Abolitionist Place. I wish the team and the next artist who will continue working on this project the best.” Brownstoner reached out to Rasheed, but didn’t hear back.

Rasheed’s proposal for the public art installation was shrouded in controversy from the get-go, with community members accusing the city’s Economic Development Corporation and Public Design Commission of lacking transparency in the artist selection and project approval, and of dismissing local input.

Nonprofit group Friends of Abolitionist Place, which helped saved neighboring 227 Duffield Street from demolition and is organizing to have it turned into a museum called the Abolitionist Heritage Center to “celebrate Brooklyn’s unique role in American Civil Rights history,” has long advocated for the inclusion of a “Sisters of Freedom” monument to be included in the park. The monument would depict significant Black abolitionist women, including Ida B. Wells, Dr. Susan Smith McKinney, Victoria Earle Matthews, and Sarah J. Garnet. A petition in support of the monument has gained more than 5,500 signatures.

Following city procedures with the Percent for Art program, the commission was offered to the artist who received the second most votes from the review panel, the DCLA rep said. While details are scant on exactly what shape Armstead’s proposal will take, it includes two installations titled “True North – Every Negro Is a Star” and “Conductors.” Armstead has described them as symbols of freedom for Brooklyn in his proposal, and said the two separate artwork concepts “work in concert.”

Armstead told Brownstoner he is still developing the final proposal and will walk through visualizations with the community at a community board meeting later this month. “It’s a great honor,” he said.

According to a description of his project shared by DCLA, “True North, Every Negro Is a Star” connects viewers with the realities of the slave trade and Underground Railroad and creates “a physical reminder, a point of light,” for each of the millions of people enslaved. “True North presents a symbol that folds the night sky, social justice in Brooklyn, abolitionism, and the Underground Railroad into an immersive experience. The retro-futuristic steel body combines historic Brooklyn swagger, freedom, education, science, technology, and the natural world,” the description says.

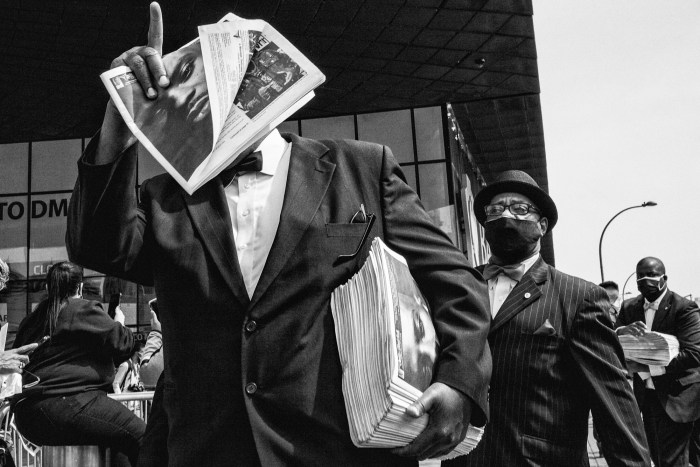

“Conductors,” which was incorporated into the project based on community feedback, depicts people in the African diaspora who helped formerly enslaved people to free themselves, allowing viewers to engage with abolitionists “face to face,” the proposal says.

Armstead said he wants to “offer a space to connect emotionally to the legacy, bravery, and humanity of enslaved Africans seeking self liberation” and create “a unique on-site experience celebrating freedom.” He added he also wants to transfer knowledge about the slave trade, Underground Railground, and abolitionism — and, crucially, Brooklyn’s role in it.

Armstead’s work has been shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art; the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; the Brooklyn Museum; the Berlin VideoFest; and other. His works are included in the collections of the African American Museum in Dallas, the Centre Pompidou, and a number of other collections, both public and private, according to his bio.

Armstead has been working with local stakeholders, including Friends of Abolitionist Place, and is still in conversation about how their visions could be wrapped into his proposal, the DCLA rep said, adding that “Conductors” could potentially include figurative representation of actual abolitionists.

Friends of Abolitionist Place member Melissa Gomes told Brownstoner the group had a video conferencing meeting with Armstead this week, and while they haven’t had a chance to collaborate yet, “he seems to be a little bit more open to the conversation regarding the art piece, and involving the abolitionists in the art piece.”

She added the group still very much wants the inclusion of the “Sisters in Freedom” monument in the park, and members are feeling positive about possible collaboration. Armstead is looking at doing a multifaceted installation that represents “the entire abolitionist movement, and the enslaved people,” she added.

Following Armstead’s presentation to Community Board 2 later this month, a community feedback process will ensue. The project will also go before the Public Design Commision for conceptual review, which includes opportunity for public testimony that could influence his design.

DCLA Assistant Commissioner for Public Art Kendal Henry said in a statement the agency is committed to “working with the community to commission a permanent public artwork for this space that pays tribute to the rich history and legacy of Brooklyn’s Abolition movement.”

“Kenseth Armstead’s compelling vision for this monument offers up a chance to commemorate both the unimaginable human toll of the Atlantic slave trade, as well as the remarkable courage of people who lived right here in New York City to stand up against this historic injustice – a fight that we continue today.”

Work on the park is a long time coming and follows controversy going back to at least 2004 when the city rezoned Downtown Brooklyn as part of its Downtown Brooklyn Plan. Using eminent domain, the city seized and demolished private houses associated with the 19th century abolitionist movement and Underground Railroad to make way for new privately developed towers and a public park named Willoughby Square over a high-tech underground parking garage. The Willoughby Square and parking project never came to pass, and eventually became what is now the under-construction Abolitionist Place park, whose name nods to the area’s abolitionist past. EDC pledged to fund a public art installation that honored the area’s history as part of the park’s construction.

The new commission won’t affect the timeline for the opening of the 1.15-acre public park, which also includes a new playground and multiple outdoor seating areas. That is still on track for later this spring.

The public art project will likely take two to three years to complete, the DCLA rep said.

This story first appeared on Brooklyn Paper’s sister site Brownstoner.