Brooklynites rallied on Wednesday to demand that city and state officials work with them — not around them — to transform the aging Brooklyn-Queens Expressway.

Gathered beside the massive highway near Red Hook, the newly-formed Brooklyn-Queens Expressway Environmental Justice Coalition said the upcoming overhaul of the roadway must be community-led, with an emphasis on environmental justice and repairing the communities divided by the expressway.

“We know that the current planning process has been a sham,” said Sebastian David Baez, an organizer with the Sunset Park-based organization UPROSE. “No proposed beautification in our neighborhoods will hide the fact that this toxic infrastructure divides our communities, that it pollutes our neighbor’s lungs, that it does not mitigate or adapt to climate change.”

The government has to seize the “once-in-a-generation” opportunity to repair the damage, he said – with the community at the forefront of the project.

The city is in the midst of planning a $5.5 billion overhaul of the crumbling triple cantilever portion of the BQE in Brooklyn Heights, which is fast approaching the end of its safe and useful life.

Local politicians have criticized the Adams administration’s proposal to add more traffic lanes to the cantilever. In January, the federal government rejected the city Department of Transportation’s application for an infrastructure grant to implement the project.

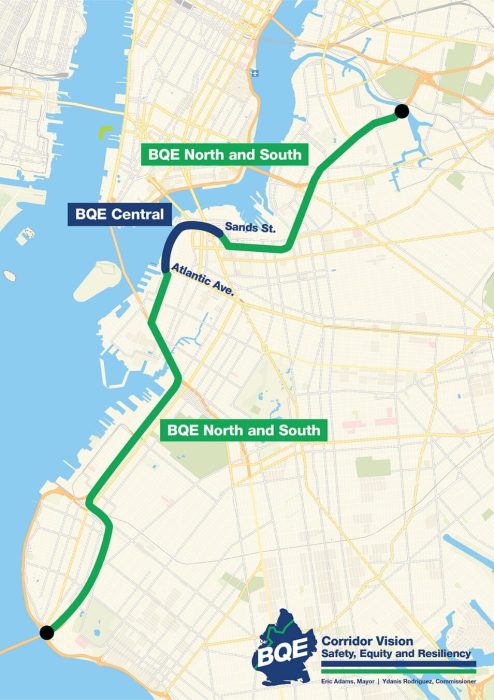

Separately, the Adams administration is developing a redesign of the 10.6 state-owned miles of the BQE north and south of the cantilever, and recently received a $5.6 million federal grant to support the continued planning of the project.

But the coalition outright rejected plans to rebuild the cantilever, and condemned the “segmented” projects — calling instead for what one member, Maria Fernanda Pulido-Velosa, called a “corridor-wide comprehensive transformation of the BQE.”

At the rally, Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso said Brooklynites affected by the BQE have been calling for change for years — but had been brushed off. Now that federal funding is on the horizon, the local community must take charge.

“We’re doing this specifically because when that money comes down, we don’t want outside interests saying or telling us what to do,” Reynoso said. “We don’t want corporations or conglomerates or groups that have never been along the corridor of the BQE to come into our communities and tell us what they think is right.”

The Robert Moses-era highway cuts through the middle of dozens of Brooklyn neighborhoods, and has been linked with high rates of asthma and other illnesses. Quincy Phillips, with the Red Hook Initiative, said Red Hook residents are “constantly” affected by the highway — which effectively cuts the neighborhood off from the rest of Brooklyn.

A Red Hook Initiative survey of hundreds of locals found that many are fearful of crossing beneath the wide highway’s raised portions, he said. The pedestrian signals are too short, and the area below the highway is dark and dirty.

Raísa Lin Garden-Lucerna, a lifelong resident of the south side of Williamsburg, recalled heading to playgrounds right under the BQE as a child.

“We were breathing in toxic air filled with particulate matter, black carbon, and fumes,” she said. “I also remember all of the asthma. Kids in my elementary school couldn’t play at gym and recess unless they had their inhalers with them.”

Garden-Lucerna advocated for “shovel-ready” projects designed by the community – like BQGreen, which would cap a portion of the BQE in Williamsburg with a park, and the Sunset Park Greenway-Blueway.

“We deserve money to implement projects created by us, not for us, because we know our communities best,” Garden-Lucerna said.

A representative for the city’s DOT said the agency supports both long and short-term fixes on the state-owned portions of the BQE — including projects like BQGreen. But while the city is working closely with the state to develop those fixes, it cannot implement them — the state is ultimately responsible for choosing and implementing any projects on BQE North and South.

“Robert Moses-era urban highways like the BQE have divided communities and NYC DOT is leading a community-driven effort to reconnect neighborhoods while making much-needed repairs to the city-owned portion of the BQE,” said DOT spokesperson Vin Barone, in a statement. “While the state owns 88% of the BQE, we support a comprehensive reimagining of the highway that reconnects communities and addresses its negative effects. NYC DOT is dedicated to delivering enhanced safety, welcoming public spaces, and sustainable transportation options throughout the corridor.”

The state DOT did not respond to a request for comment.