It’s not exactly a New York minute…

City environmental bigwigs are now estimating that construction of a massive tank and filtration facility designed to help keep the noxious Gowanus Canal clean after its federal scrub won’t be completed until the end of 2032, according to government emails and letters obtained by Brooklyn Paper.

Both the filtration facility and the eight-million gallon cistern, which come as part of the federal government’s plan to cleanse to fetid waterway, are meant to capture and sanitize raw sewage and stormwater runoff, but they won’t be fully built until Dec. 31, 2032 — two decades after the feds first floated the proposal.

Despite the far-off deadline, the city’s chief environmental guru called the new 12-year construction timeline “compressed” and “aggressive,” citing various other projects that the city’s Department of Environmental Protection is working on simultaneously.

“Please note that this schedule is compressed, and we have concerns proceeding on such an aggressive construction timeline, particularly when DEP is already heavily loaded with mandated and other major projects,” wrote DEP Commissioner Vincent Sapienza on Aug. 12 to his federal counterpart, Environmental Protection Agency Regional Administrator Peter Lopez.

The plans emerged after the city requested a delay of between 12 and 18 months on the tanks in July, citing a COVID-19-related budget shortfalls.

Federal EPA officials have warned the city that the repeated delays — which date back long before the viral outbreak — violated federal orders under the Superfund cleanup program, and could incur “significant” penalties, a lawyer for the agency told a local watchdog group on Tuesday.

“The penalties under Superfund may be significant and EPA is trying to be cognizant of the fact that the city has certain financial burdens at the moment and weighing that against noncompliance which stretches back for several years before the COVID-19 issues,” said Brian Carr at the monthly meeting of the Gowanus Canal Community Advisory Group on Sept. 22.

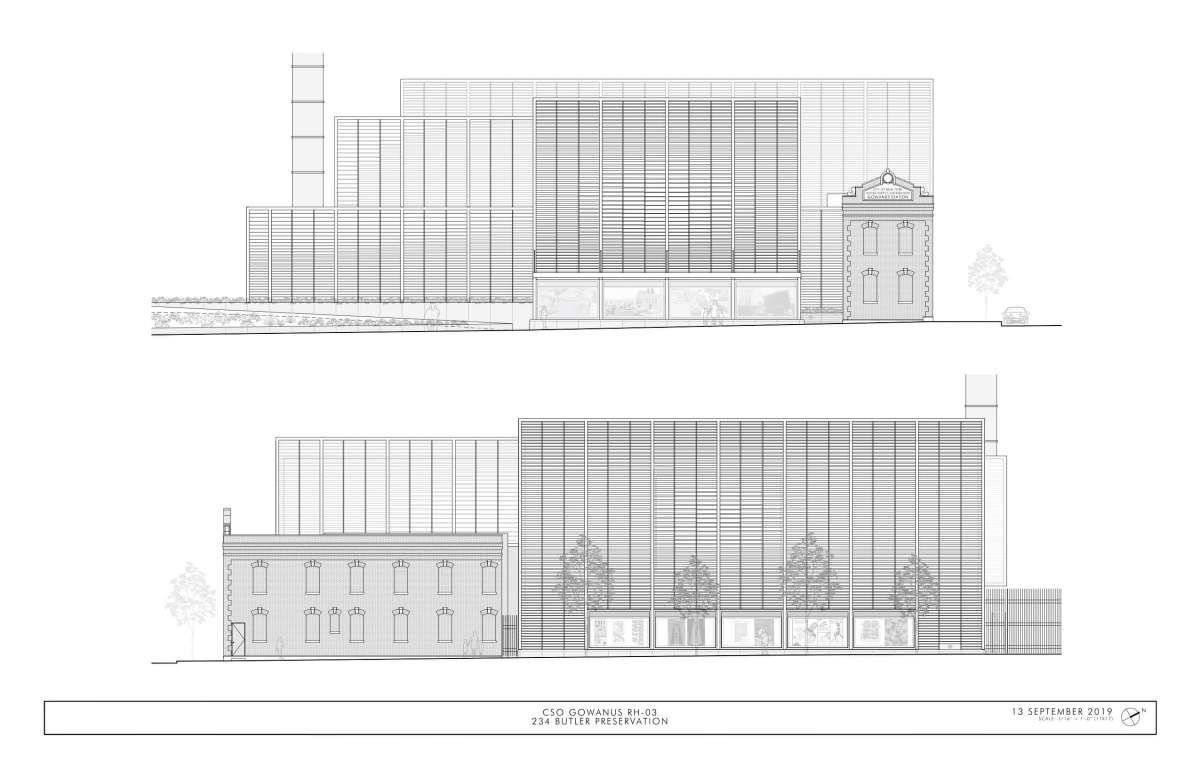

The city was also supposed to provide more detailed designs for the upper tank and the treatment site planned at Butler and Nevins streets, known as the head house, by Aug. 18 — but officials blew past that deadline, and six days later sent an outdated and incomplete rendering from last year, correspondences between the agencies show.

Members of the CAG were incensed by the hold ups, with one waterfront advocate calling for municipal bureaucrats to be locked up for their tardiness.

“Personally, I don’t want to see a financial penalty because we’ll all have to pay by way of taxes. I say throw somebody into jail,” said Louis Kleinman of the nonprofit Waterfront Alliance.

In several written responses DEP rejected EPA’s accusations claiming the setback for the head house designs was due to the feds and state preservationists foisting stricter requirements for preserving part of the historic Gowanus Station building at the facility

“We strongly disagree with EPA’s statement that DEP is not in compliance with its Superfund obligations. DEP has consistently met its milestones, and any delays that have occurred have been the result of new requirements imposed by EPA,” wrote Sapienza on Aug. 12.

Lawyers for both agencies continue to hash it out, according to Carr, and EPA is evaluating the city’s extension requests.

The upper cistern along with a smaller four-million gallon tank at the canal’s Fourth Street Turning Basin are designed to catch the city’s combined sewer overflow, which dumps 363 million gallons of raw household sewage and polluted stormwater runoff into the 1.8-mile canal each year.

The smaller tank’s schedule is still largely to be determined, but DEP anticipates completing design and permitting for that structure within five years, according to Sapienza.

The infrastructure upgrade will cost a whopping $1.3 billion in city funds, $748.5 million for the upper cistern and head house, and $558.5 million for the mid-canal tank, according to DEP calculations.

Both barrels will keep the channel from filling back up with gunk as the feds tasks historic local polluters — mainly the city and National Grid — to excavate, clean, and cap the canal bed, slated to start this fall.

But taxpayers could end up footing a higher bill due to the delays, according to EPA’s project manager for the cleanup, Christos Tsiamis, who said that the city would have to pay for dredging any additional viscous toxic material known locally as “black mayonnaise” flowing on top of the new cap in the decade to come.

“That will cost New York City a lot of money to go 10 years later and remove whatever it has deposited there,” Tsiamis said.

Under the city’s schedule, contractors would start demolishing the existing historic Gowanus Station building that currently lives at the Butler Street site in January of 2022, and officials will have to preserve and reassemble two brick corner facades of the century-old structure and incorporate them into the new facility.

The recent delays are not the first for the city. In 2018, DEP proposed building a 16-million-gallon tunnel beneath the canal instead of the tanks, which stalled progress for the original plans the better part of two years, before Lopez ultimately rejected the tube in 2019.

Last spring, DEP also tried to get away with using faux-aged materials to recreate the 106-year-old building’s brick exterior in an effort to save time and money, but EPA also rejected that cost-cutting scheme, saying there were enough old cinder blocks to salvage and reuse them for a corner facade of the building, along with the ornate terracotta pediment at Nevins Street.