“It’s a very exciting moment and it’s a relief,” said Nasser, a Brooklynite of Yemeni descent who did not give his last name. “Hopefully, this new administration builds on the foundation that this country is set for.”

The executive order, signed by former President Donald Trump in 2017, placed stringent travel restrictions on citizens of Syria, Iran, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, Somalia, and Sudan seeking to enter the United States. Trump argued that the ban would curb terrorism, but critics called the move discriminatory and callous, especially as residents of Syria and Yemen sought refuge amid the countries’ civil wars.

Civil rights organizations lobbed a series of court challenges against the restrictions, but while one court challenge removed Iraq and Sudan from the banned list, none overturned the ruling. The Supreme Court upheld the Trump’s order in 2018.

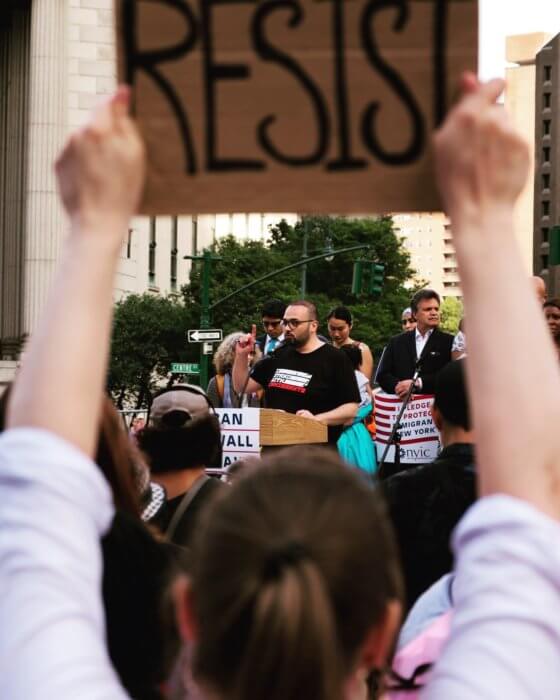

After the ban’s announcement in Jan. 27, 2017, Yemeni bodega owners and immigrants rights groups took to the streets in protest, rallying around Borough Hall and Manhattan’s Washington Square Park. The restrictions lit a fire under the Yemeni community, one Arab leader said.

“That’s one thing that came out of this ban: the Yemeni community is very much politically engaged,” said Rabiyaah Althaibani, a Bay Ridge activist who founded a political consultant firm called Arab Women’s Voice. “That’s because we came out and said, ‘Listen, we need your votes!'”

Nasser, whose father and uncle run the popular restaurant Yemen Cafe, said that the anxiety about the ban was palpable at the restaurant’s Cobble Hill and Bay Ridge locations the day Trump signed the order.

“It was very shocking,” he said. “People were like, ‘Are we really going back to this?'”

It was difficult enough getting relatives out of Yemen. Because of the war, the US embassy was closed, and the country’s only operating airport in the southern city of Aden was often shut down, according to Althaibani, who spent years helping her husband get a visa.

To escape the country, many Yemenis had to take a treacherous boat ride to Djibouti. Many applied for their US visa from there, while others traveled to Egypt and Malaysia, where there were also US embassies. All the while the war raged on, killing 233,000 people as of December mostly from starvation and lack of health services.

Althaibani’s now ex-husband, a prominent Yemeni journalist, was able to escape via boat to Djibouti, and spent two and a half years in India and Malaysia trying to get a US visa. He was finally granted a waiver in 2018 because his life was at risk as a journalist, but many others weren’t so lucky.

“I went to the press; I wrote op-eds on it, and a big part of it too is that they gave him waivers because his life was in danger,” she said. “There were so many Yemeni families who had sick relatives and they were denied.”

While some Yemenis with means traveled to other countries to await their visas, like Althaibani’s ex-husband, many others stayed in Djibouti, the most expensive country in Africa. The extended stays have put a significant financial strain on Yemeni families, Althaibani said.

“They have to support an entire family in Djibouti, which is really expensive, for four years,” she said. “They sold everything to go to all these embassies.”

Everyone in Althaibani’s circle was affected by the ban, she added.

“I don’t know a single Yemeni family who doesn’t have either a relative or a friend who is banned. Everyone I know,” she said.

The restrictions also affected residents in Bay Ridge and Bensonhurst from Syria and the other banned counties, an immigrant rights advocate of Palestinian descent explained.

“I was not directly impacted by the Muslim ban, but my community and friends were, and it was devastating,” said Bay Ridge local Murad Awawdeh, who co-runs the New York Immigration Coalition.

Awawdeh said he had one Syrian friend couldn’t travel home to see his dying father, and another who was separated from his wife and child in Yemen for years as the war raged on and the COVID-19 pandemic began.

“It’s an incredibly hard situation to be in in this moment,” he said.

The repeal of the ban was a welcome change, but it must be accompanied by more sweeping reforms in order to be effective, Awawdeh argued.

“On top of everything — the backlog — you have COVID and things are just moving incredibly slow,” he said. To hasten the process for foreigners who’ve already waited for more than four years to have their visas approved, the least the government can do is expedite the approval procedure, Awawdeh added.

“I think going to those people and not making them start all over again and helping them with the process … that would look like justice in this situation,” he said.

But that might be tough given the staffing cuts the State Department sustained during the Trump administration.

“Trump gutted the State Department, so there are a lot of positions to be filled,” Althaibani said.

“Just look at your Yemeni neighbor your bodega owner who is in pain,” she said. “No matter how much of a centrist Biden is, look at that difference.”