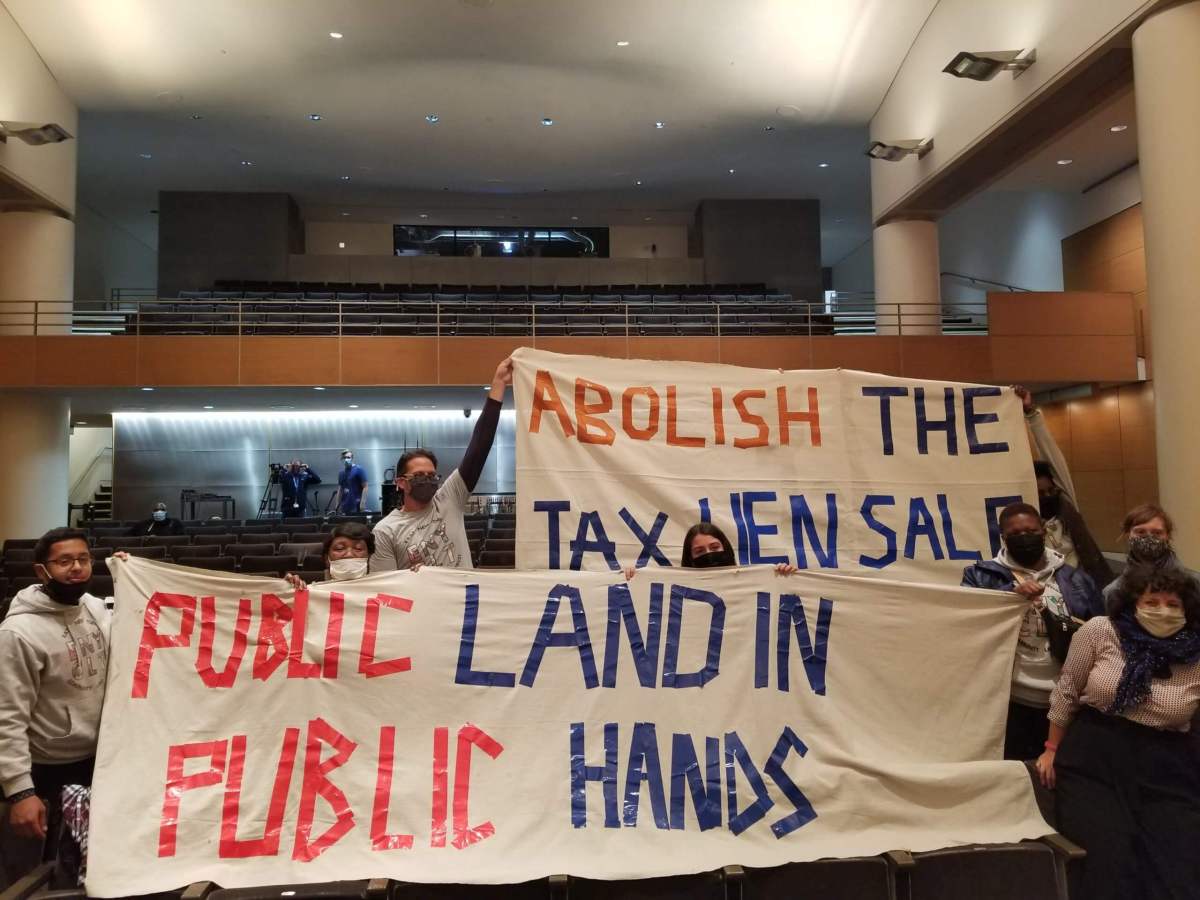

The city’s Racial Justice Commission held its final public input meeting for Brooklynites at the Brooklyn Museum Monday night, but the affair quickly became a lesson in organizing strength as speaker after speaker called on the commission to propose banning the controversial tax lien sale, and to prioritize community land trusts in the city’s dispensation of public land.

As the commission — empaneled earlier this year to identify areas of city law perpetuating structural racism and recommend charter revisions to correct them — inches closer to proposing final charter amendments for the November 2022 ballot, members of the East New York Community Land Trust (ENY CLT) one-by-one approached the commissioners and gave versions of the same speech, calling the transfer of vacant public land to private developers and the sale of distressed property tax debt to investors a prominent example of institutional racism being baked into the city’s laws.

“As it stands, long-term Black residents of East New York and Brownsville are being systematically displaced due to speculative investment by for-profit developers with no ties to the community, and most do not give back to our community in a meaningful way,” said Izoria Fields, a lifelong East New Yorker and ENY CLT’s vice president, in testimony to the Commission. “We implore you to lead the way in adjusting the Charter to prioritize transferring public land to community land trusts and fight to revamp the tax lien sale process in a manner which helps protects us and our neighbors.”

The commission has been holding public input sessions for months to hear from New Yorkers on how racism inflects everyday life, and specifically how city law and institutions can propagate it. Last month, it released a preliminary report identifying six broad areas of inequity encompassing the topics brought up by residents: access to quality public services, distribution of resources across neighborhoods, professional advancement and wealth-building, marginalization and over-criminalization, representation in decision-making, and enforcement and accountability for government and other entities.

Commissioners have said that they want the ballot proposals to be as broad as possible to eliminate structural racism as much as can be done by revising the charter. The commission is now holding a final set of hearings ahead of releasing its proposals next month, along with a possible preamble to the charter to establish guiding values of anti-racism for the city to abide by.

Monday’s meeting was sparsely attended, except for those with ENY CLT, who said they organized to show up as a unit to drive home just how positive an impact they feel the commission could have by putting their priorities on the ballot.

“We believe East New York is not for sale. And we envision a healthy and sustaining community where our people come before profit,” said ENY CLT secretary Deborah Ack. “Planning and development in East New York and Brownsville should be led by us for us, the longtime Black and brown residents of East New York and Brownsville.”

The group contends that both the public land transfer program and the tax lien sale put New Yorkers of color at a disproportionately high risk of displacement. Since 1996, the city has farmed out debt collection on unpaid property taxes to the private sector, selling homeowners’ tax lien debt to a trust run by the Bank of New York Mellon to collect the debt, and can foreclose on properties that don’t pay up. Relatedly, the transfer program allows the city to transfer publicly-owned lots to for-profit developers at little to no cost, often for $1.

These transfers mean the arrival of new management, which often can mean higher rents and subsequent displacement. Oftentimes, a distressed property owner will sell to pay off the debt, but that still leaves their tenants at risk of eviction under new management.

These programs disproportionately impact communities of color: a 2018 map by the nonprofit 596 Acres shows that $1 lot transfers are heavily concentrated in Black and Latino areas of the city, including Central Brooklyn, Southeast Queens, the South Bronx, and Upper Manhattan.

“We realize what happened in Bed-Stuy, we know what happened in Bushwick,” said the land trust’s president, Albert Scott, referencing gentrification in those neighborhoods. “It has been demonstrated by giving it to the for-profits, they have been pushing us out. Time and time again.”

The community land trust model would have the public lots be managed and maintained by a consortium of local residents developing the property as affordable homes rather than a speculative asset, advocates say, arguing that that would allow the properties to remain permanently affordable and prevent gentrification in low-income areas like East New York and Brownsville. For the tax lien sale, ENY CLT says the job of debt collection should be returned to the public sector.

The next tax lien sale is scheduled for Dec. 17, after having been delayed several times during the pandemic.

Several commissioners maintained that they were impressed by the group’s organizing strategy, and that they now have a lot to consider before proposing final ballot measures.

“I thought they were very effective at reinforcing the points of concern and what they see as doable solutions,” said Jennifer Jones Austin, the commission’s chair, in an interview with Brooklyn Paper. “And they gave us something to work with.”